An Illustrated ThING WITH INFORMATIONS

Introduction

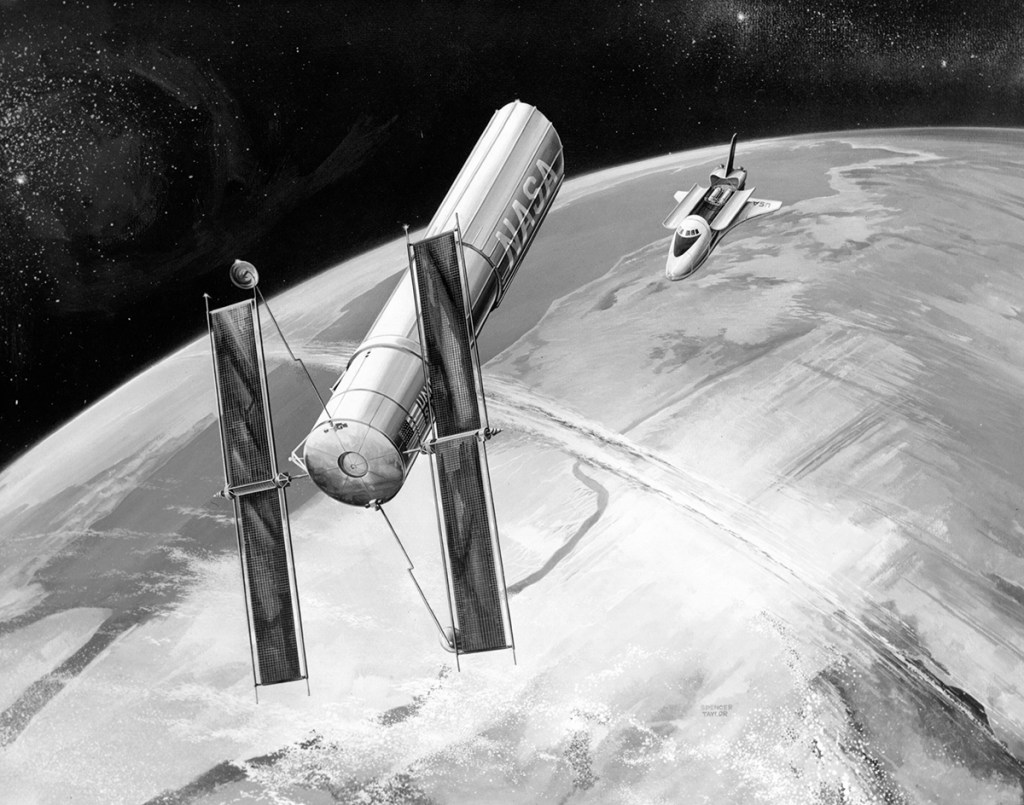

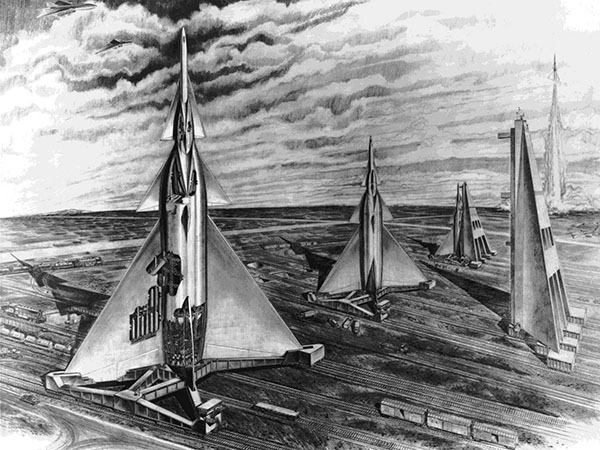

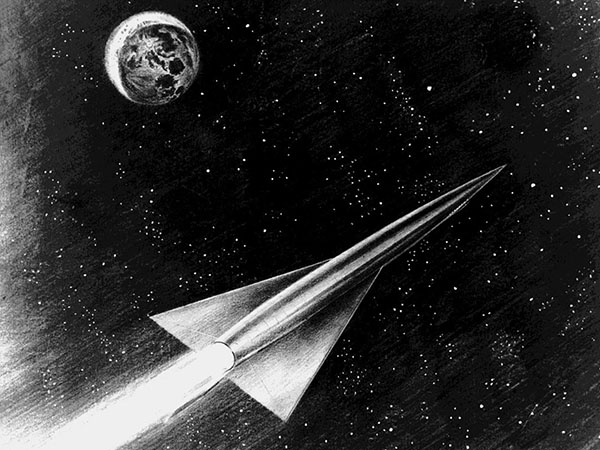

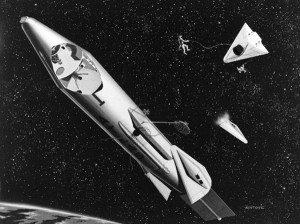

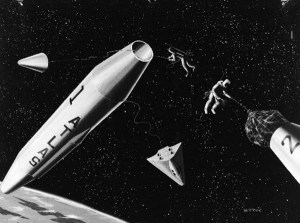

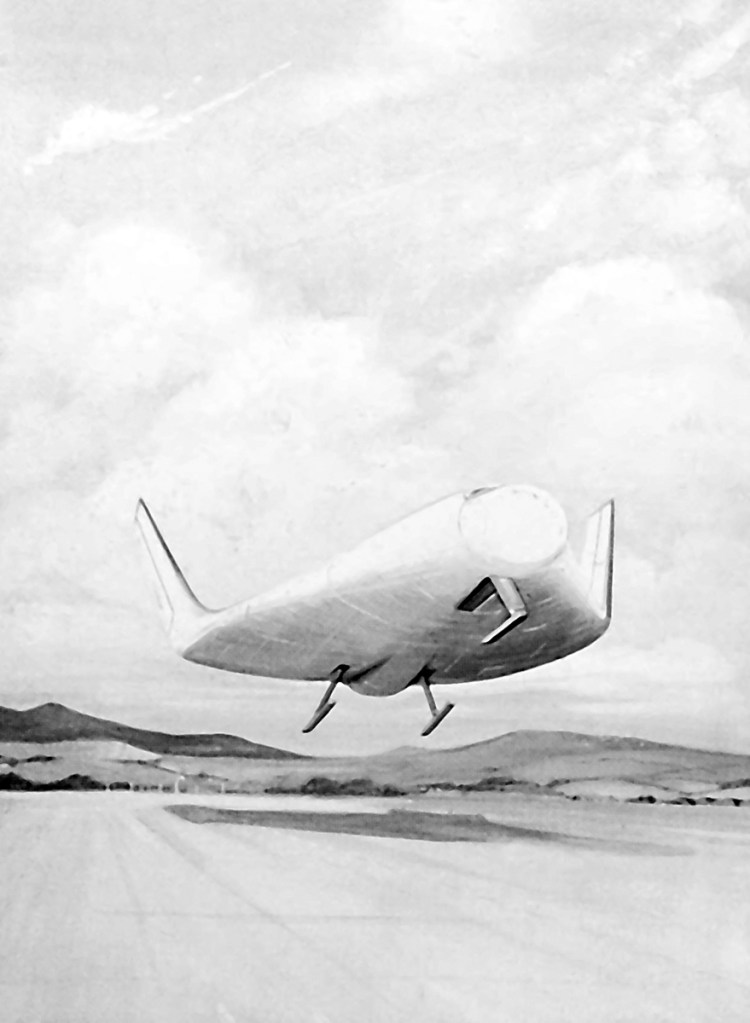

Concept art by Spencer Taylor.

I honestly thought knocking up an illustrated history of the shuttle would take me an afternoon, and I was wrong. Very wrong. There’s a lots of backstory. But if we’re going to talk about this, you need to know about that, and the other thing, know what I mean?

The thing with the shuttle is, there is no great speech that spurred a nation forward, no watershed moment, no great need. It’s hard to know where to start, where it begins. Instead, the first space worthy orbiter was a coalescent of decades of half-starts, what-ifs, and “if we can’t have that, can we have this?” It has no father or mother, but it has uncles, aunts, and lots of those cousins you’re not supposed to talk about at the dinner table.

So here is what I think is a mostly correct, potted history of the Space Shuttle. It is neither exhaustive, nor authoritative, but the artwork is beautiful and that’s why you’re here. Right?

Background

Writing about the space program is like writing an Indiana Jones movie. It just doesn’t work without Nazis. So, we’ll start the story in 1936 with some Nazis….

Silbervogel 1936-1944

In the mid-thirties, an Austrian engineer named Eugen Sänger – a Nazi – published a series of articles on rocket-powered flight for the Austrian journal Flug. Those articles attracted the attention of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium, the Reich’s Aviation Ministry. Sänger’s ideas had potential for the Amerikabomber project, an initiative to obtain a strategic bomber capable of striking the United States from Germany. The RLM gave Sänger his very own research institute near Braunschweig where, aided by mathematician Irene Bredt, he developed a sub-orbital rocket bomber, the Silbervogel. Launched from a rocket-powered sled at 1,200mph, the Silbervogel would climb under its own power to an altitude of approximately 90 miles, accelerating to approximately 13,500mph. As it glided back into the stratosphere, the increasing air density would generate lift against the fuselage causing it to bounce and regain altitude. Aerodynamic drag would begin to slow the vehicle, each bounce being shallower than the last, but the vehicle would still be able to cover vast distances.

While the Reich Air Ministry rejected Sänger’s 1941 initial report due to its size and complexity, a greatly reduced version of that report submitted to the RLM in 1944 represents the first serious proposal for a vehicle capable of reaching the edge of space.

BoMi 1952-1956

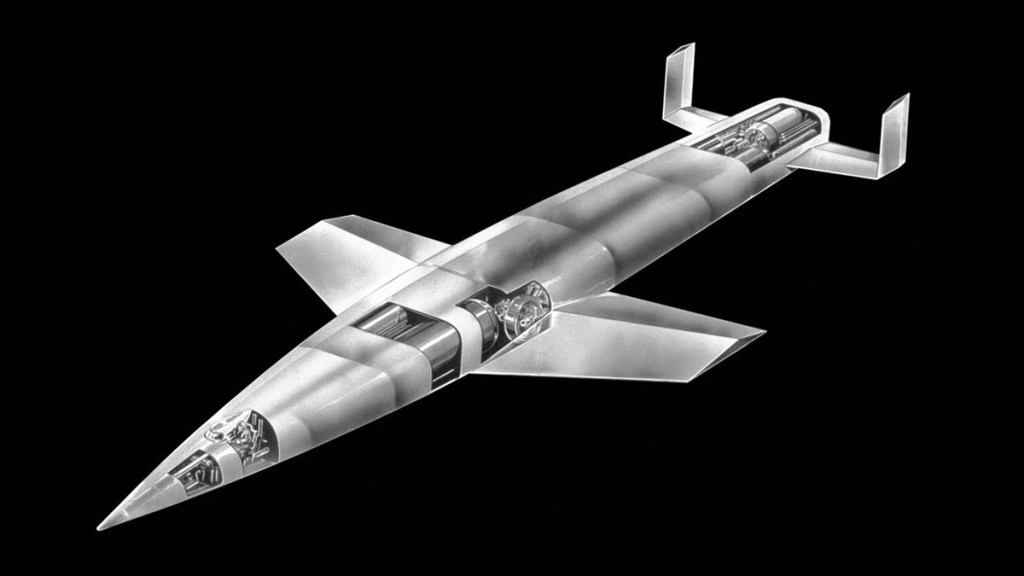

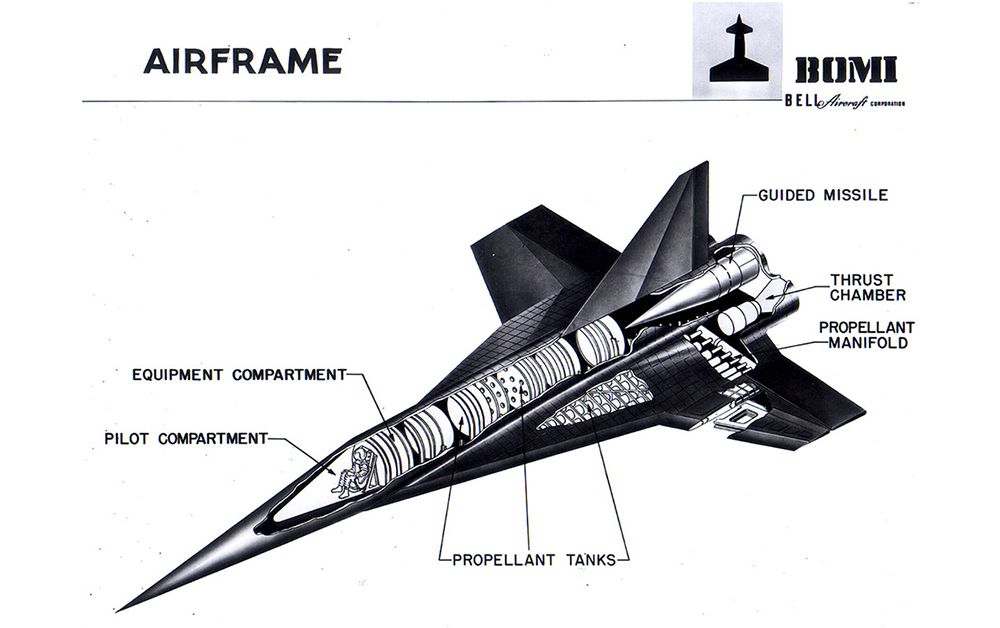

In 1952, Walter Dornberger and Krafft Ehrikke at Bell Aircraft proposed a vehicle based on Sanger and Bredt’s research. Dornberger had led Nazi Germany’s V-2 program and other projects at Peenemünde, where Ehrikke had worked as a propulsion engineer. In essence, their proposal was a vertically launched version of the Silbervogel, known as Bomber Missile or Bomi. By 1956, BoMi had evolved into three separate programs:

RoBo, or Rocket Bomber, an updated version of BoMi.

Brass Bell, a long-range reconnaissance version.

Hywards (Hypersonic Weapons Research and Development Supporting system), a smaller prototype system to develop the technologies needed for Robo and Brass Bell.

Von Braun Ferry Rocket – 1952

For the Colliers series of articles and subsequent books, Von Braun proposed a sleeker, more elegant version of a launch vehicle he’d conceived of in 1948.

The three-stage rocket lauched vertically, after a short interval the autopilot would tilt the rocket to a shallow angle while still climbing. At an altitude of 24.9 miles the first stage separated, a fine steel-mesh ribbon parachute deployed, slowing the tail section towards a gentle water landing. The second stage separated when the vehicle reached an altitude of 40 miles. The cabin-equipped reusable third stage would continue under its own power to an altitude of 63.3 miles when its engines would cut out , momentum carrying it to orbit. At an altitude of 1,075 miles, a 15 second engine burn would stabilize its orbit. Reentering tail first to an altitude of approximately 50 miles, the pilot would level off, holding attitude to allow air friction to slow the vehicle from 13,300 mph to 5,760 mph. At an altitude of 15 miles, now travelling at 750mph, the pilot would begin a series of descending turns toward the landing site, touching down at approximately 65mph.The first and second stages would be recovered at sea for refit and reuse.

Goodyear METEOR – 1954

In 1954 Goodyear Aerospace’s Darrell Romick and two colleagues introduced a concept model of a three-stage spaceplane, the third stage achieving earth orbit, at the annual conference of the American Rocket Society. Each stage would contain landing gear and a crew of its own, allowing each to be piloted to landing for reuse. Launched at White Sands, the first booster stage would separate 300 miles downrange at an altitude of 24 miles, the second stage 700 miles farther at 41 miles, with the third stage continuing to orbit.

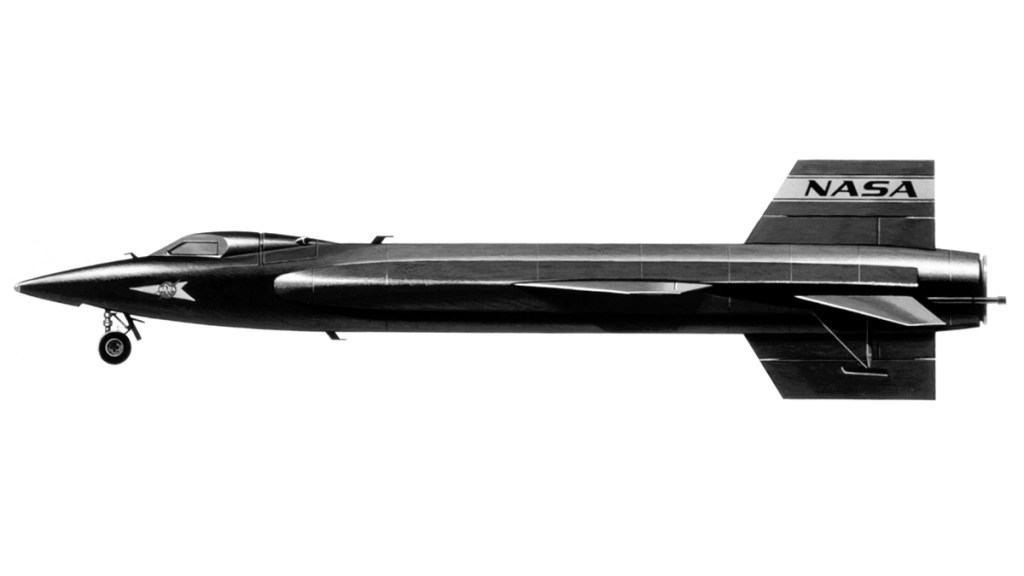

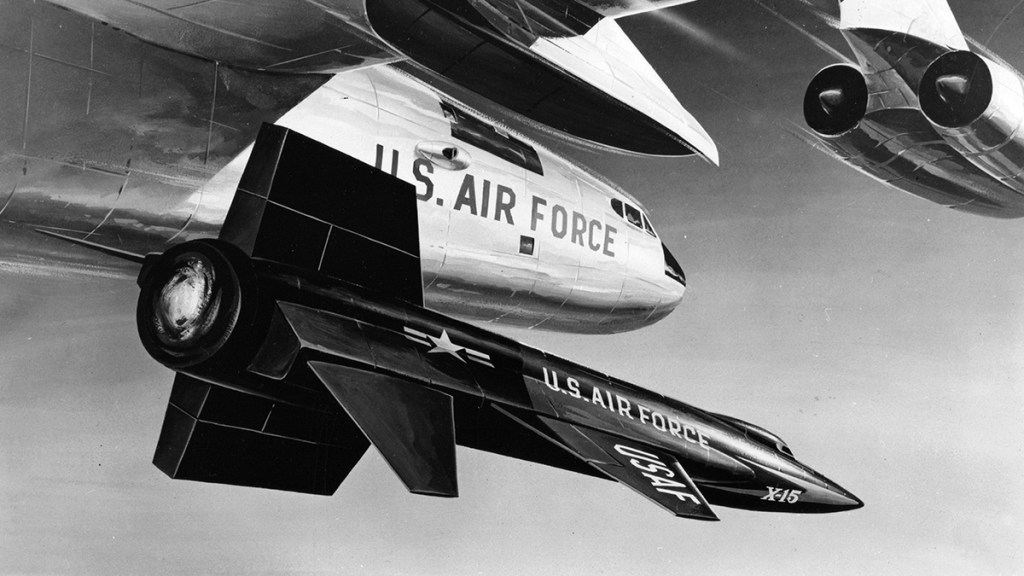

X-15A 1954 – 1968

The X-15 was based on a concept study prepared by Dornberger for the NACA on hypersonic research aircraft. RFPs were published in 1954 for the airframe, and 1955 for the engine. North American Aviation won the contract for the airframe in 1955, Reaction Motors was contracted to build the engines in 1956. The aircraft first flew in 1959, and over the course of the program eight of its twelve pilots earned astronaut wings for flights above the Kármán line. As early as 1957, an orbital version of the X15 was considered by the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC) at Wright Field based on a proposal by North American engineer Harrison Storms.

Convair Shuttlecraft – 1957

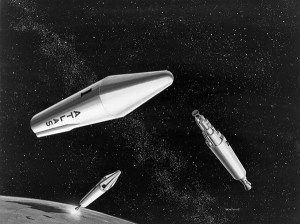

Having moved to the Astronautics Division of Convair, Krafft Ehricke proposed a three-stage shuttlecraft capable of carrying a pilot and four passengers on ferry missions to resupply Earth satellites.

“Ready for launching, the satelloid would be a three-stage rocket, with the third stage having a deltalike wing and a sealed cabin outfitted for flights up to a week. After the first and second stages were fired and dropped, the third stage would take up its orbital path. To return to earth, the satelloid would be stalled down through the atmosphere at a very high of attack to reduce forward speed and prevent excessive heating. Even so, skin temperatures of around 2000 degrees would be experience and a multiwalled cabin would be required to keep the occupants cool.“

-Popular Mechanics, Mar, 1957

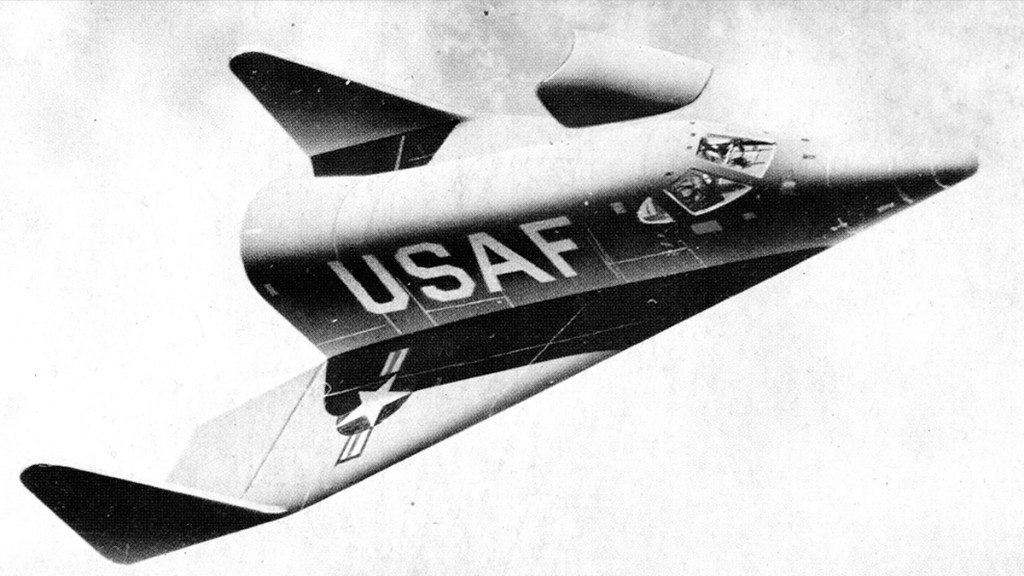

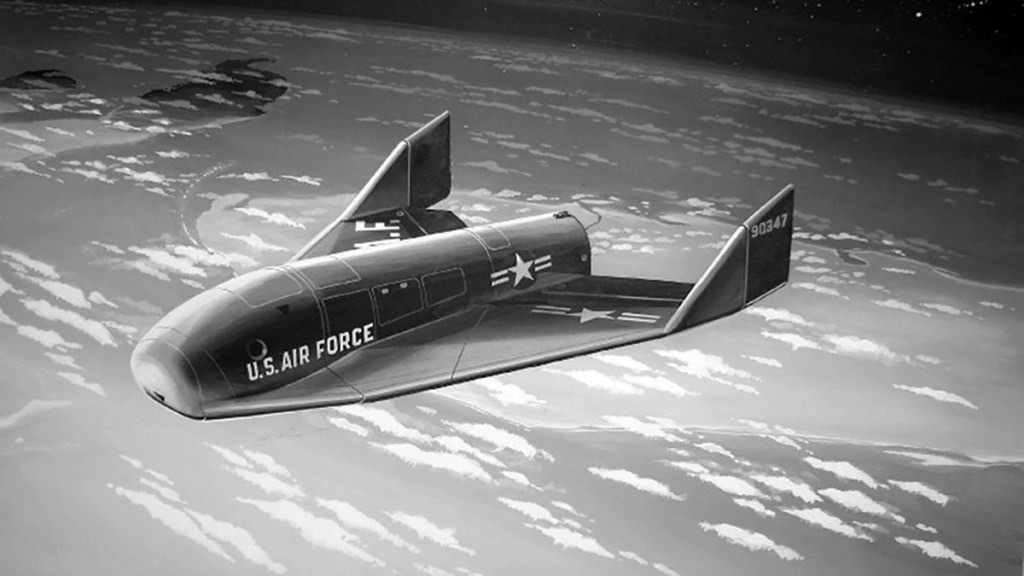

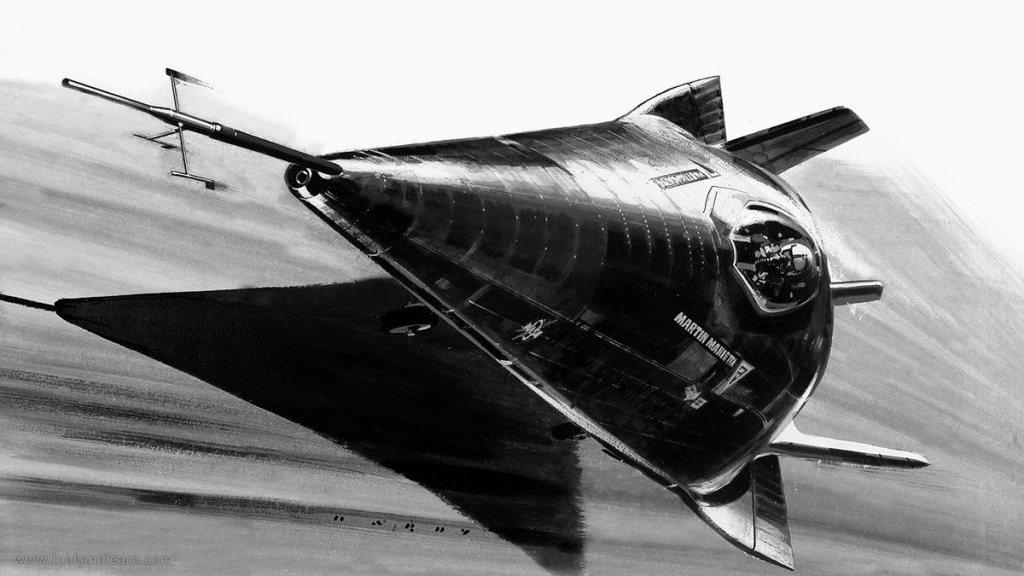

X-20 Dyna-Soar 1957-1963

Left: After aerobraking in the atmosphere, the opaque heatshield protecting the window is jettisoned so the pilot can see the fucking ground. Right: Bell Aircraft artist concept.

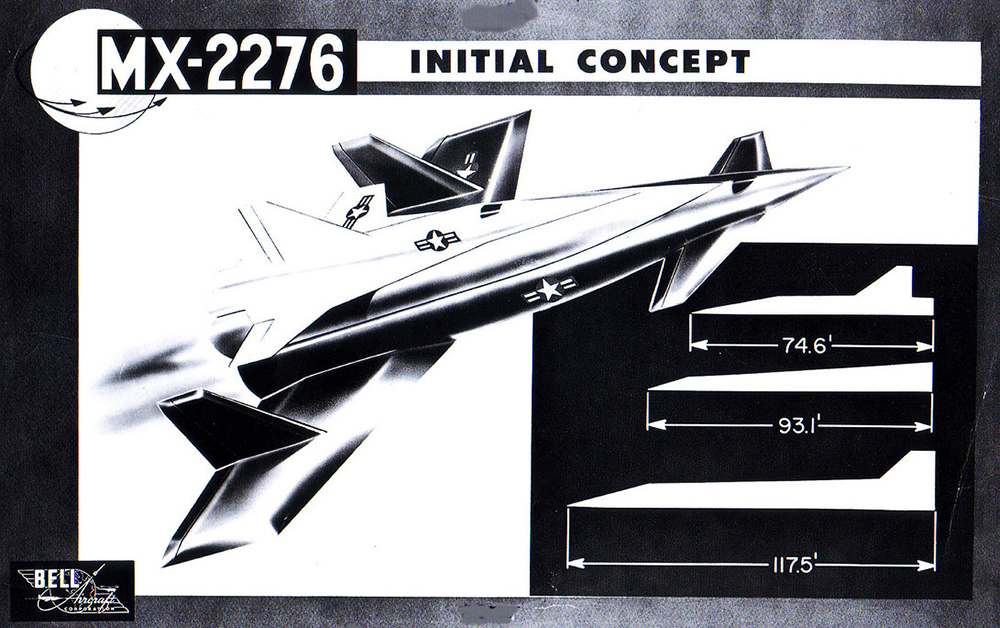

After the launch of Sputnik in October 1957, the USAF Air Research and Development Command (ARDC) consolidated the RoBo, Brass Bell, and Hywards studies into the Dyna-Soar project, or Weapons System 464L. In 1958 nine contractors tendered bids for the project, the field eventually being narrowed to just Bell and Boeing. Despite six years of continuous research at Bell, the contract was awarded to Boeing in June of 1959. The overall design was outlined by Boeing in 1960. The vehicle would have a tail-less low-wing delta shape. A single pilot sat at the front, with an equipment bay behind containing reconnaissance equipment, weapons, or a four-person mid-deck depending on the mission. The frame and upper surfaces would be constructed of René 41, a nickel-based alloy, the lower surfaces covered by molybdenum sheets placed over insulated René 41. An expendable Martin Marietta upper stage attached aft of the vehicle would allow orbital maneuver and a launch abort capability.

Now designated X-20, Dyna-Soar was unveiled to the public at an event in Las Vegas in 1962. Eight months before drop tests were to begin, politics, and the lack of clarity over its mission led to its cancellation in December 1963 by then Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara.

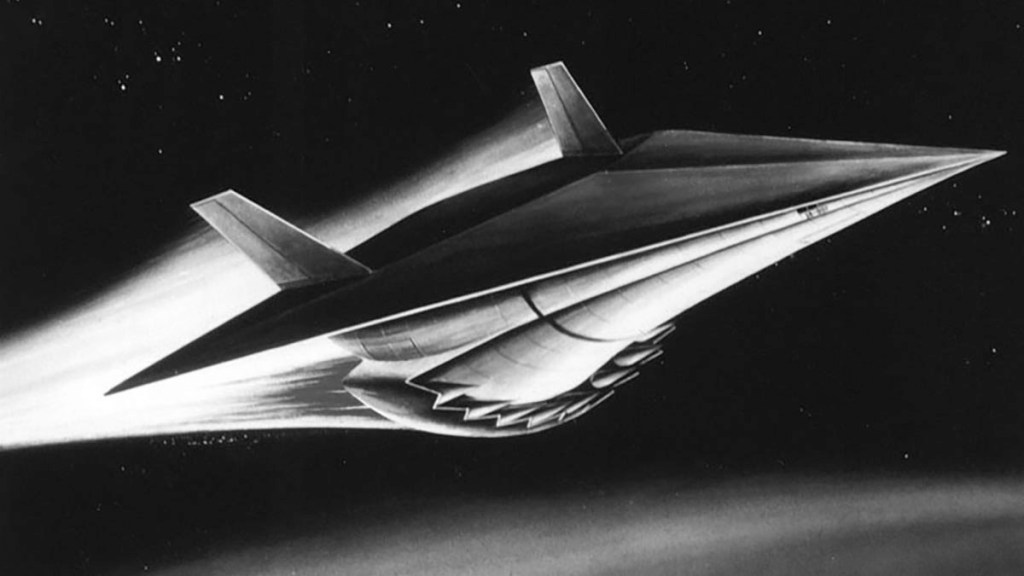

Aerospaceplane 1957-1963

An attempt to develop an air-breathing single-stage-to orbit spaceplane at Wright-Patterson AFB, led to a 1957 DoD funded for a recoverable launch booster. By 1959, it had evolved into the Recoverable Orbital Launch System or (ROLS), a single-stage-to-orbit horizontal-take-off-and-landing vehicle. A liquid air cycle engine (LACES) would liquefy air on its ascent to use as an oxidizer for rocket fuel at altitude. Further testing revealed that better performance could be achieved by extracting pure oxygen from the liquified air. Research contracts were issued to Marquardt and General Dynamics to develop the Air Collection and Enrichment System (ACES) with Garret AirResearch designing and building the heat exchanger.

Boeing, Douglas, Convair, Lockheed, Goodyear, North American, and Republic were awarded study contracts to develop a single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) vehicle capable of horizontal take-off and landing. With a crew of three, and a twelve-meter cargo bay, the vehicle was to be operational by 1970. Developmental realities forced the Air Force to drop its requirement for a single-stage vehicle in 1962. In June 1963 Douglas, General Dynamics, and North American each received funds for continued study, with Martin receiving a contract from the Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory to build a full-scale wing-fuselage structure. In October that year, the USAF SAB concluded that the existing state-of-the-art was insufficient to develop the Aerospaceplane in a reasonable time and did not request funding the following year.

ATLAS Orbital System – 1958

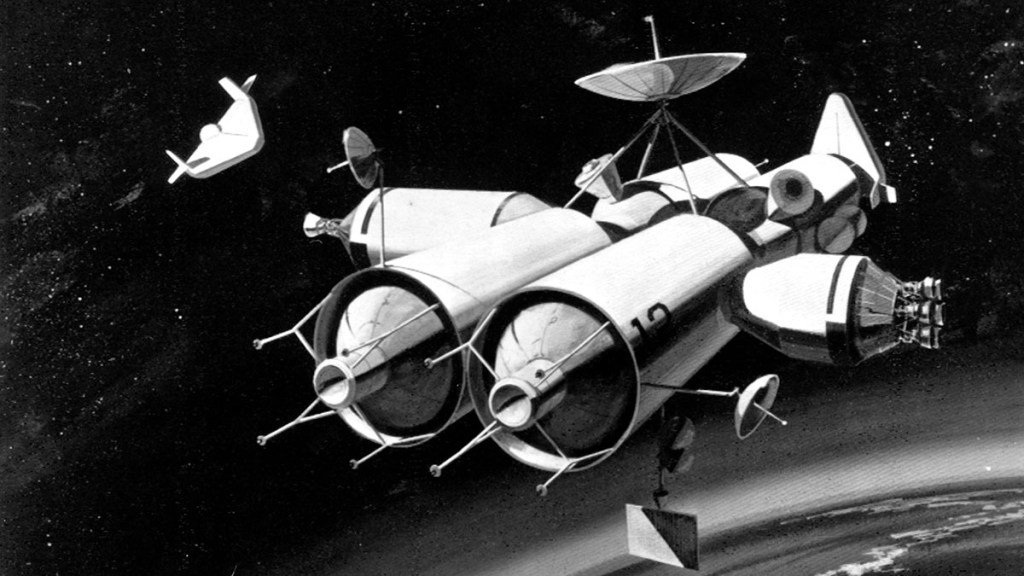

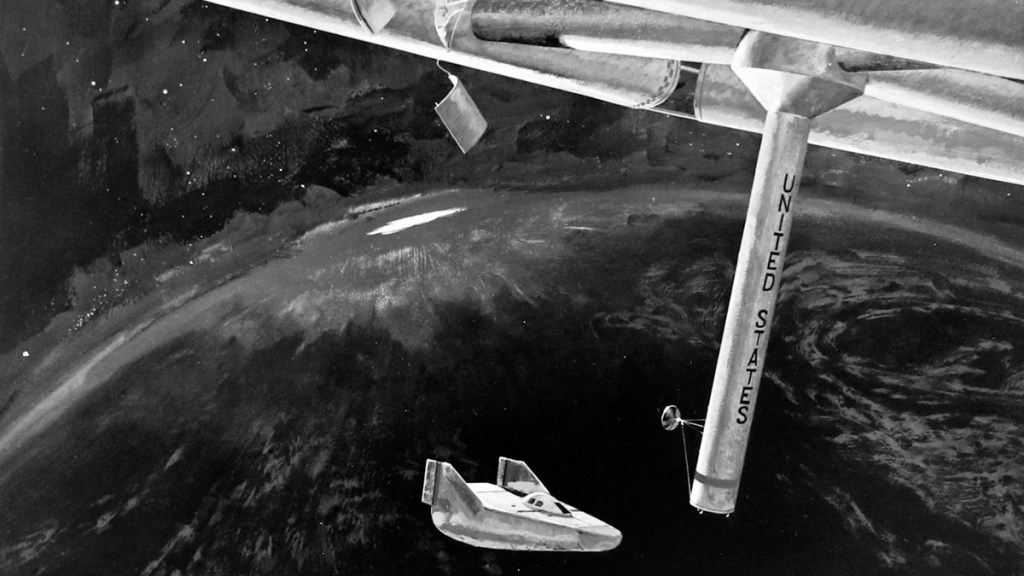

Less than a year after the Atlas ICBM began flight tests Krafft Ehricke proposed an ingenious solution to building an orbiting space station which, as Mercury had yet to fly, no one really needed. Since no booster capable of delivering a space station to orbit existed, Ehricke proposed modifying the forward propellant tank1 of an Atlas to accept an inflatable rubber nylon structure, providing insulation, and subdividing the tank into rooms. The space station’s own booster would become it; the station. The four-story habitat would accommodate a laboratory, sleeping quarters, a kitchen/day room and a khazi. Fitting out the Outpost was expected to take about a week: the first four-man crew would rendezvous with the spent rocket in a personnel module comprising of two manned gliders boosted by a primary Atlas stage and a second Centaur stage. An unmanned cargo module carrying supplies would arrive separately.

After installing battery power, water, and oxygen systems delivered by an unmanned cargo module the crew would depart. Subsequent crews would deliver and inflate the pressurized habitat module and complete the fit out. The final crew would install a SNAP-2 nuclear reactor and fire vernier thrusters, spinning the station to create artificial gravity, making it operational.

National Aeronautics and Space Act 1958

The Eisenhower Administration split the United States’ military and civil spaceflight programs, which were organized together under Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established in July, replacing the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), giving the United States space development effort a distinctly civilian orientation. NASA absorbed the core of NACA employees, as well as the Naval Research Laboratory’s Project Vanguard, the Army’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Army Ballistic Missile Agency.

Space Task Group 1958

In November, a working group of NASA engineers was established to manage Project Mercury and future US space endeavors.

NASA Studies 1962-1964

In 1962 NASA began to fund studies for space station logistics vehicles, including the “Reusable Ten Ton Orbital Carrier Vehicle” or RTTOCV.

Douglas Astro

Douglas Astro as visualized by (left) Ron Simpson and (right) Ken Hodges. The Simpson painting was reproduced on a lenticular airmail stamp issued by the Kingdom of Bhutan in 1970.

The Astro was a VTHL TSTO system designed to support space station operations using designed around existing hardware from the Apollo and other US space programs.. Both stages were manned lifting body vehicles.

Lockheed RTTOCV

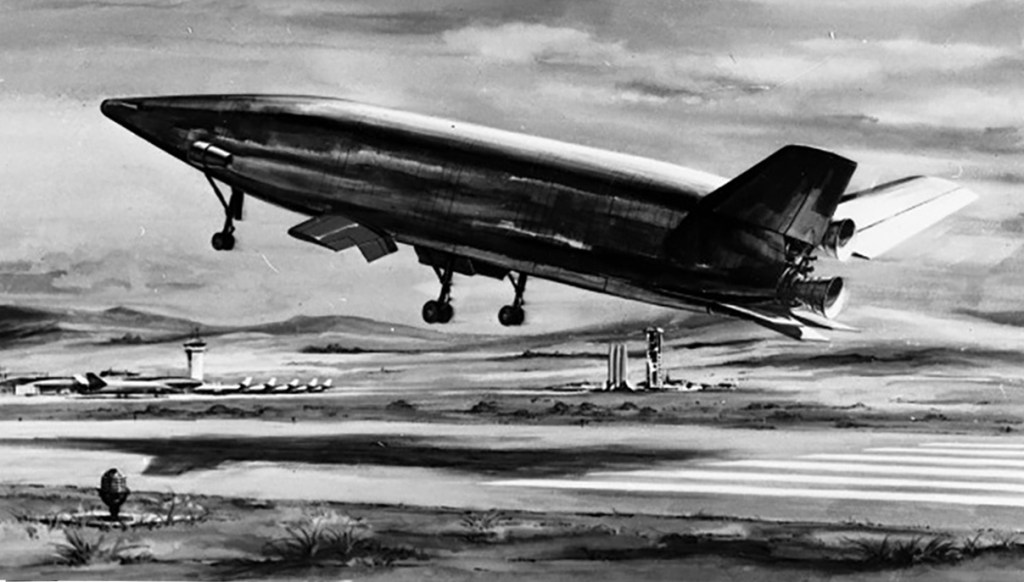

Lockheed proposed a two-stage winged vehicle based on a classified Air Force study it conducted in 1958 in co-operation with Hughes Aircraft. Lockheed’s final design was boosted by a sled-launched rocket plane.

Lockheed Space Taxi

Lockheed proposed replacing the Apollo CSM with ten-man reusable spaceplane while retaining the Saturn IB booster as a means of reducing the cost of NASA’s space station, lunar base, and other activities in the seventies. Fully reusable system options included a sled-launched HTHL TSTO rocketplane or a ramjet-rocketplane deploying the interorbital Space Taxi.

McDonnell Space Plane

McDonnell’s study of 1963 proposed three vehicle options, launched on either Titan 3M or Saturn IB launch vehicles. The first two were based on McDonnell’s Gemini capsule, the latter was a winged vehicle capable of carrying a crew of two and up to four passengers.

NAA RTTOCV

North American’s final design of 1963 was a lenticular orbiter carrying two pilots and up to ten passengers.

NASA Lifting Body Research 1962-1972

NASA M2-F1, the original lifting body aircraft was built as an in-house NASA Dryden project on a budget of $30,000. The aircraft was of tubular steel construction, covered with a mahogany plywood shell with landing gear taken from a Cessna 150. After towing the M2-F1 behind a Pontiac convertible, air tows behind a NASA C-47 began in August 1963. The success of the program led to NASA’s development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies, the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by Northrop. In 1967, the M2-F2 was severely damaged in a landing accident after an unpowered glide test. Redesigned with a third center fin to improve stability, and re-designated M2-F3, it flew again in June 1970.

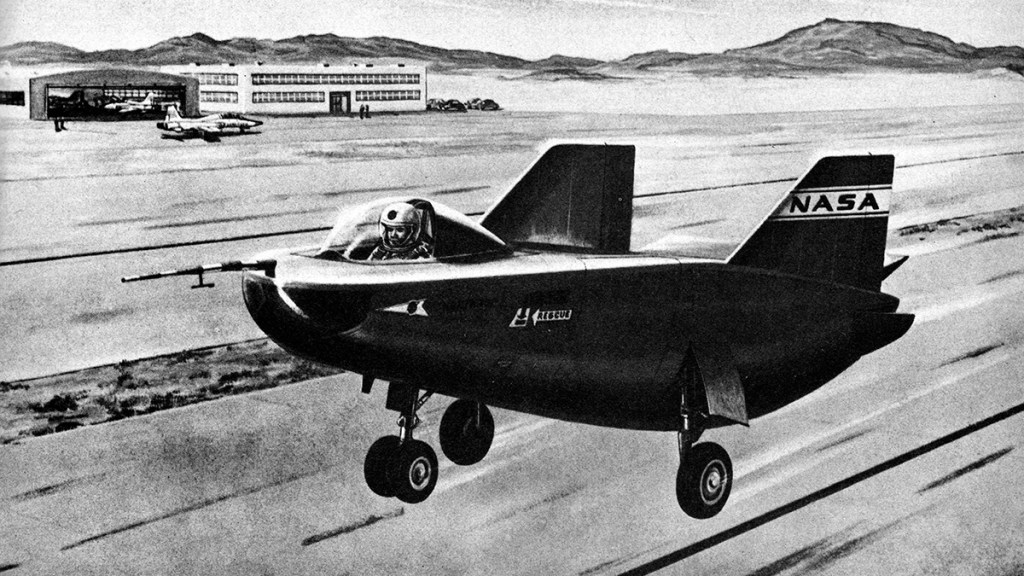

PILOT 1963-1975

Martin-Marietta X-24 painted by Wilf Hardy for Look and Learn.

The X-24 was built by Martin Aircraft Corporation as part of a joint US Airforce-NASA program called PILOT. The X-24A was the fourth lifting body design to fly, making its first flight in 1969. After 28 flights, the vehicle was returned to Martin (now Martin Marietta) and rebuilt as the X-24B, testing FDL hypersonic configurations which promised to double the hypersonic lift-to-drag ratio of the X-24A. On its own initiative, Martin Marietta built two jet-powered versions of the X-24A envisioned as training airframes, dubbed SV-5J, which were never flown.

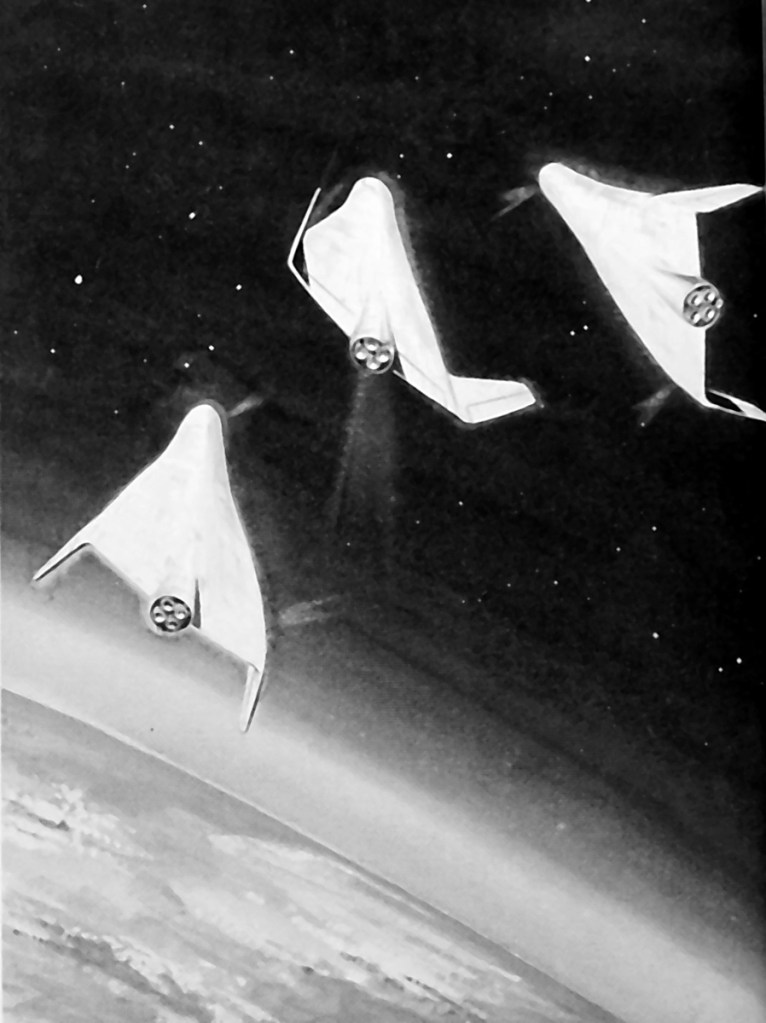

BAC MUSTARD 1964-1967

The Multi-Unit Space Transport And Recovery Device or MUSTARD was a reusable launch system concept explored by the British Aircraft Corporation. Mustard would launch vertically; the hypersonic spaceplane modules would progressively separate during ascent. The final spaceplane would be capable of achieving a sub-orbital trajectory before performing a controlled re-entry.

AACB 1965-1966

After Aerospaceplane was terminated, the USAF Flight Dynamics Laboratory began studying less ambitious spaceplane designs, which led to a series of studies funded by the joint NASA / DOD Aeronautics and Astronautics Coordinating Board. The final report was issued in 1966 and suggested that reusable launch vehicles be developed in a series of classes:

AACB Class I Partially reusable vehicle launched either by existing Titan or Saturn boosters. The vehicle would accommodate up to six astronauts, carry a payload of up to 900 kg, and be available for space station crew transfer and resupply by 1974.

AACB Class II Fully reusable, two-stage-to-orbit launch vehicle. Both stages powered by LOX/LH2 engines, the vehicles would be ready by 1978, and capable of placing a payload of 9,100 kg in orbit.

AACB Class III An advanced concept using two air breathing stages to achieve orbit. The AACB concluded that the technology to develop the Class III vehicle did not exist, and the vehicle would not be available until 1982 at the earliest.

The Class I vehicle became the preferred option of the AACB, given that it had the lowest development risk, and cost.

ILRV 1967-1968

Between 1967 and 1968, the US Air Force issued study contracts for “Integral Launch and Re-entry Vehicles” or ILRVs:

FDL ILRV

In late 1968 the USAF Flight Dynamics Laboratory proposed a stage-and-a-half concept with an external drop tank.

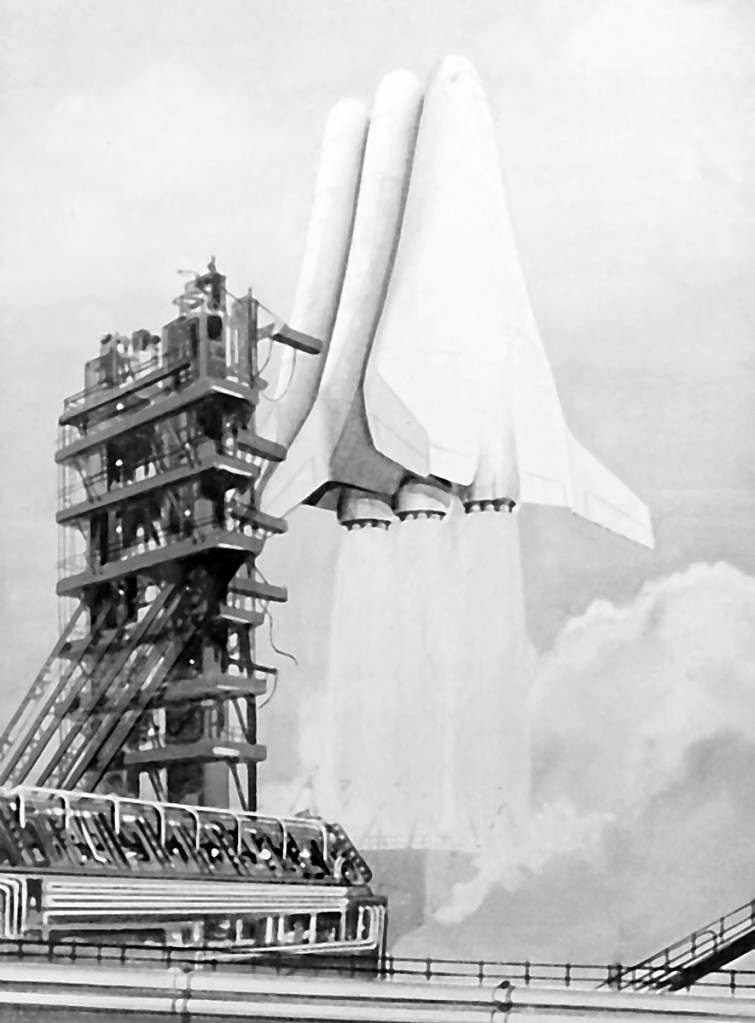

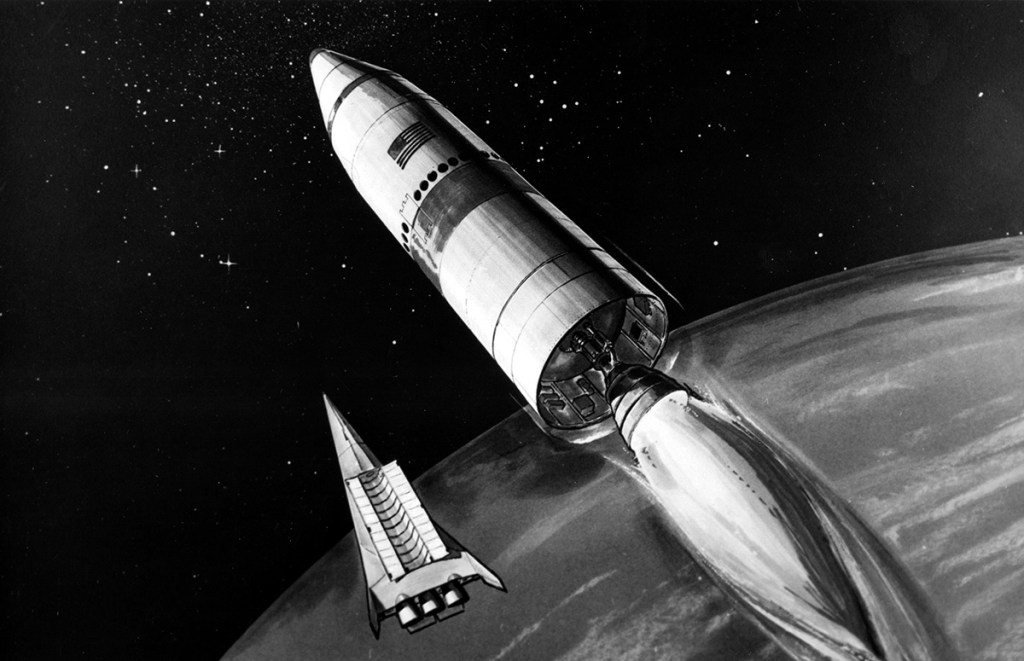

General Dynamics Triamese

General Dynamics dusted off a design originally developed for a classified 1965 USAF SAMSO project. The system was composed of three nearly identical booster / orbiter elements. Two vehicles would supply propellant for the engines of all three units during ascent. The orbital element continued to orbit with its engines fed by its own internal propellant supply.

McDonnell Douglas ILRV

McDonnell Douglas proposed a wedged-shaped ILRV orbiter, equipped with fold-out wings to improve handling during approach and landing.

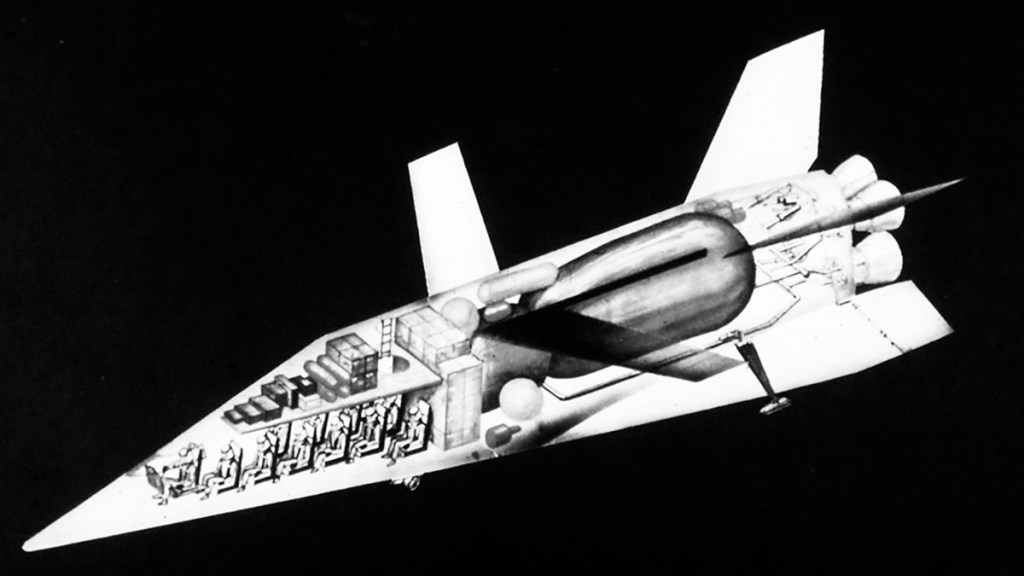

Lockheed Star Clipper

STAR Clipper, Lockheed’s ILRV design was an elaboration of a design proposed by Max Hunter in 1966. The vehicle was based on the X-24B, powered by a linear aerospike engine, with a wraparound drop tank. George Mueller, NASA’s Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, presented a downsized version of the design at a British Interplanetary Society meeting in August 1968. Mueller described the vehicle as a “space shuttle” primarily intended for space station crew transfer and resupply missions.

References

Recoverable Booster Proposals Tony Landis, AFMC

TAXI TO VENUS? Popular Science Mar. 1957

Satellite with crew? By 1965, U.S. experts say Popular Science Dec. 1957

Notes

- Ehrikke knew a thing or two about tanks. He’d spent quite a few years touring Europe and Russia in Panzers. ↩︎

One thought on “Space Shuttle: Part 1”