Many more informations

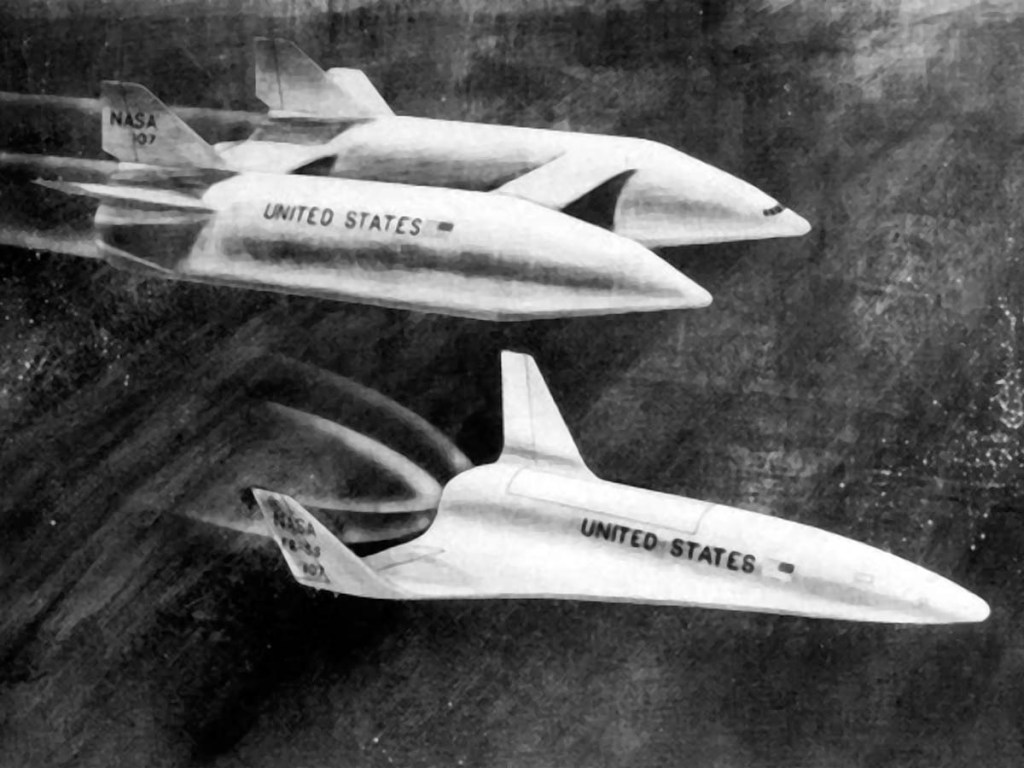

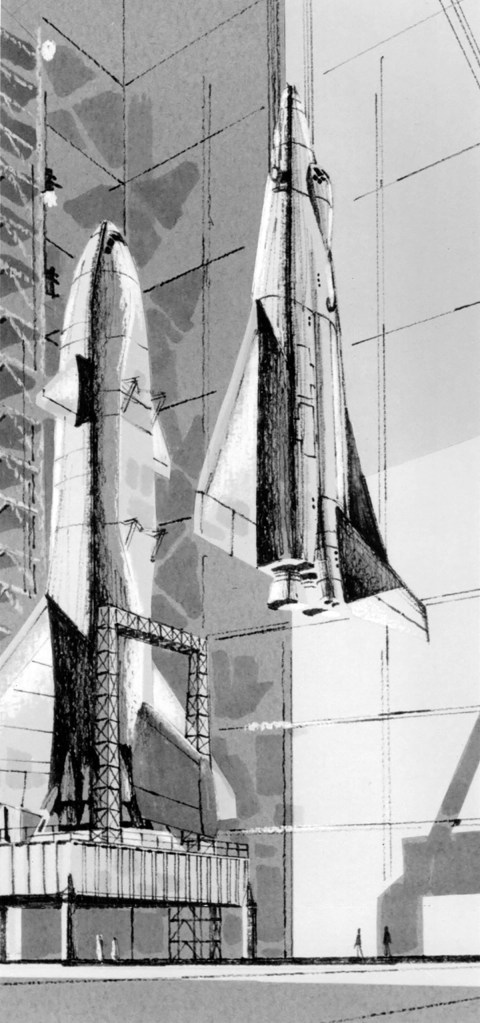

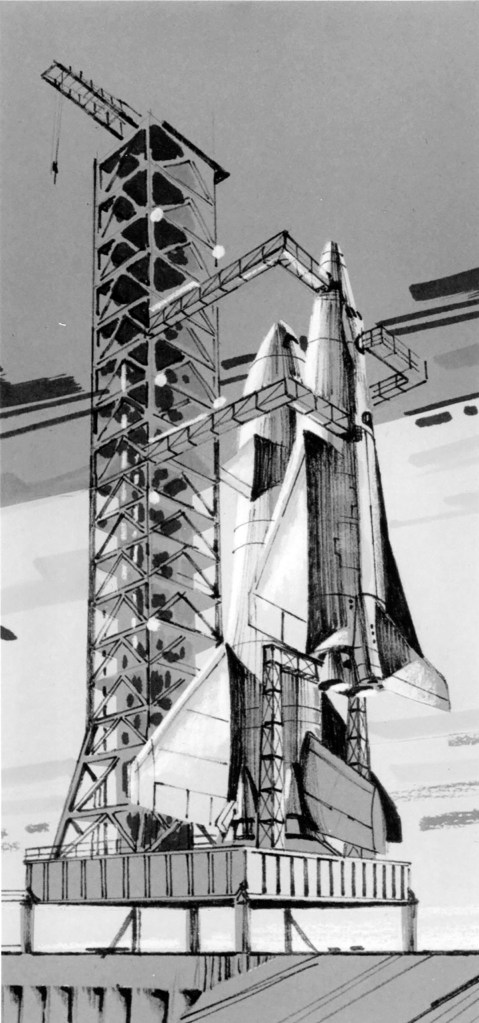

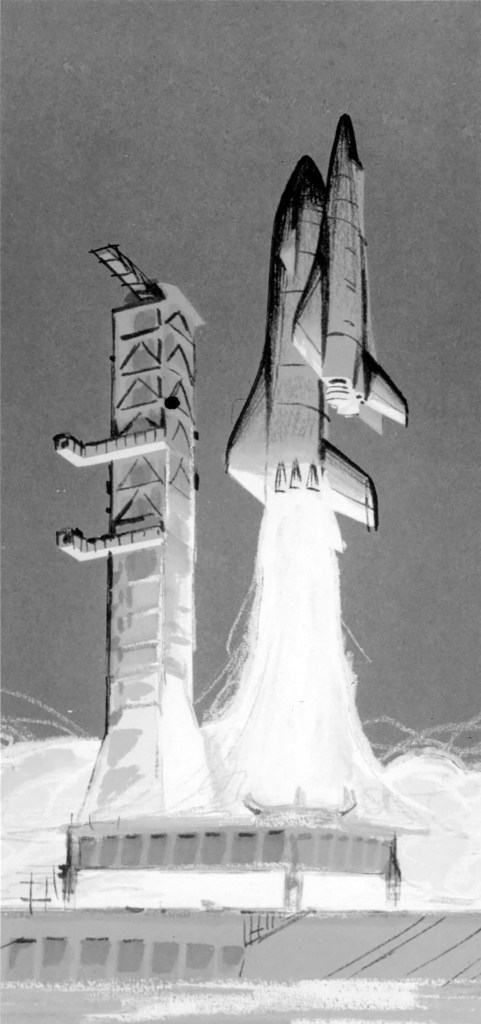

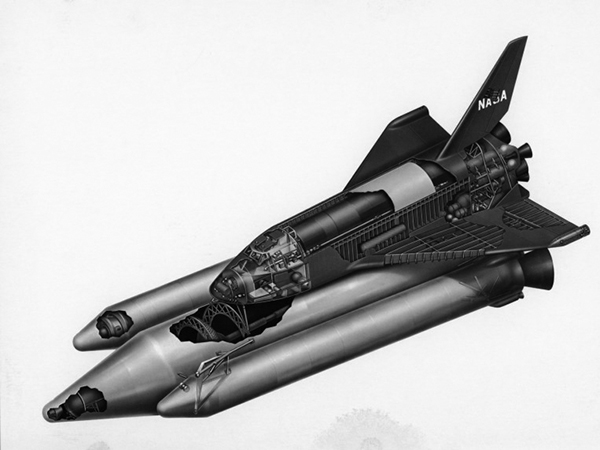

Concept art by Ron Simpson.

December 1968 – Phase A

In December 1968, NASA convened the Space Shuttle Task Group which set out the basic missions and characteristics of a reusable launch system, borrowing the term ILRV from the Air Force studies. Development would take place in four phases; Phase A: Advanced Studies; Phase B: Project Definition; Phase C: Vehicle Design; and Phase D: Production and Operations.

Each of the agencies involved favored different configurations for the shuttle: The FDL and Draper Laboratories favored a swept delta wing spaceplane, like the Dyna-Soar, for maximum cross range on re-entry. NASA Langley and Edwards AFB favored a lifting body, based on the HL-10 then under test which had a weight advantage but lower cross range.

A Request for Proposal was issued jointly by NASA Houston and NASA Huntsville in January 1969, for an eight-month Phase A study. General Dynamics, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, Martin Marietta, and North American Rockwell won ILRV study contracts. The ILRV was to be capable of delivering propellent, propulsive stages and payloads to orbit, orbital launch and retrieval of satellites, satellite maintenance, space station logistical support and short duration crewed missions. The report considered three classes of vehicles: reusable orbiters launched on expendable boosters, stage and a half vehicles and two-stage vehicles where both the booster and orbiter were fully reusable. Martin Marietta’s design was ultimately dropped, but they continued to develop their vehicle using company funds.

General Dynamics

After further study, General Dynamics abandoned the Triamese design in September as it had proven difficult to make one aerodynamic shape serve both as a booster and orbiter. After a contract extension, the company settled on a more traditional two-stage v-tailed design.

Lockheed

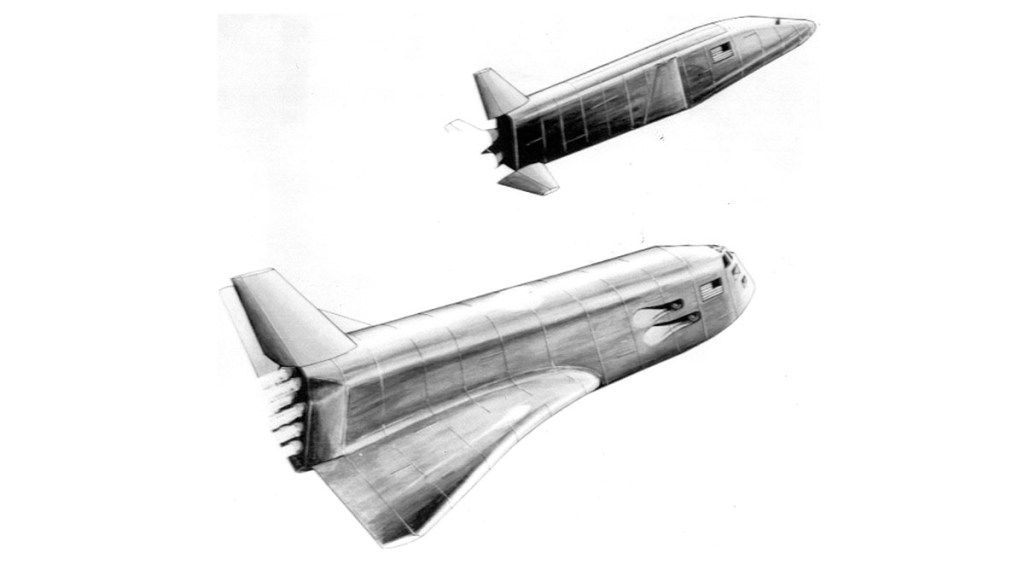

Lockheed’s Phase A contract concentrated on fully reusable versions of the STAR Clipper. Their final design was a delta-planform lifting-body orbiter paired with a body-wing booster.

Martin Marietta

Martin Marietta developed the Spacemaster, an orbiter based on the X-24B with an unusual catamaran style booster.

McDonnell Douglas

McDonnell Douglas studied partially reusable designs early in Phase A, receiving additional funding in July 1969 to investigate Langley’s HL-10 Lifting Body. The company additionally proposed a number low cost designs. The “drawbridge” orbiter would re-enter with folded wings for high cross-range military missions, and unfolded wings for low cross-range missions when the heat loads would be lighter. A smaller alternative design was derived from their 1968 ILRV proposal.

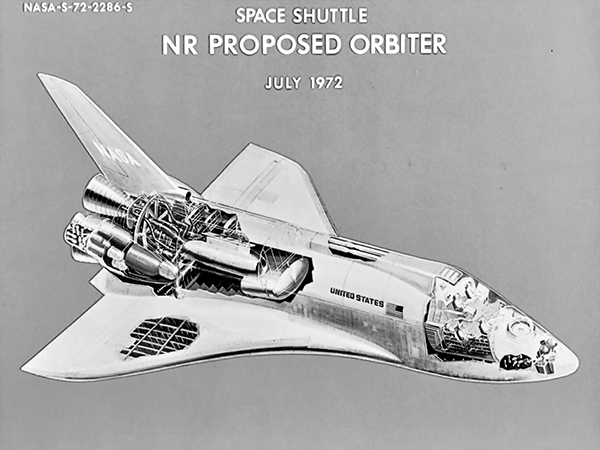

North American Rockwell

Initially focused on partially reusable designs, in June North American received additional funding from NASA to investigate a concept by the Manned Space Center’s Maxime Faget. Faget disliked the lifting-body designs for their poor low speed handling and believed they would be difficult to develop. Faget’s more conventional design was flat-bottomed with low-mounted swept wings. The vehicle would re-enter the atmosphere in a nose high attitude, presenting its lower surfaces to the airflow to blunt its descent. As the vehicle reached the lower atmosphere, it would pitch forward to a conventional flying attitude with jet engines powering the vehicle to a landing. He called his design the DC-3. In July, North American received additional funding to develop modular space station and space base concepts.

October 1969 – USAF Involvement

The cancellation of the X-20 in December 1963, and MOL in June 1969 left the Air Force without a manned space program of its own and demonstrated a need to cooperate with NASA in order to place military astronauts in orbit. NASA in turn sought Air Force support. In October NASA and the Air Force agreed to develop a reusable space vehicle that would meet both civilian and military requirements, and in so doing create a national system.

As development progressed, Air Force involvement began to shape design. The Airforce high cross-range requirement necessitated a large delta wing, which effectively eliminated the DC-3 and FR-3A from consideration.

January 1970 – Clearing House

A meeting was held in Houston to study all the in-house concepts. Over the next year, several designs were dropped including the entire series of lifting-body derived vehicles.

July 1970 – Phase B

NASA now stipulated a fully reusable system with both component vehicles being able to undertake ferry flights between landing and launch sites, ending any consideration of a partially expendable system. Funding was awarded to consortiums led by North American Rockwell, and McDonnell Douglas. In addition, both teams were instructed to study alternate orbiters: the straight-wing low cross-range Faget design and delta wing configurations for high cross-range missions.

McDonnell Douglas / Martin Marietta

Martin Marietta’s booster was derived from an alternative Spacemaster booster concept, with jet engines mounted inside the forward canard to improve weight distribution during recovery. The all-metal orbiter featured a large delta wing and a single vertical stabilizer.

North American / General Dynamics

The NAR 130 straight-wing low cross-range design remained as a secondary option as late as 1971.

NAR 134-B was a high cross-range vehicle with a payload capacity of 9,072kg, capable of making powered or unpowered glide landings.

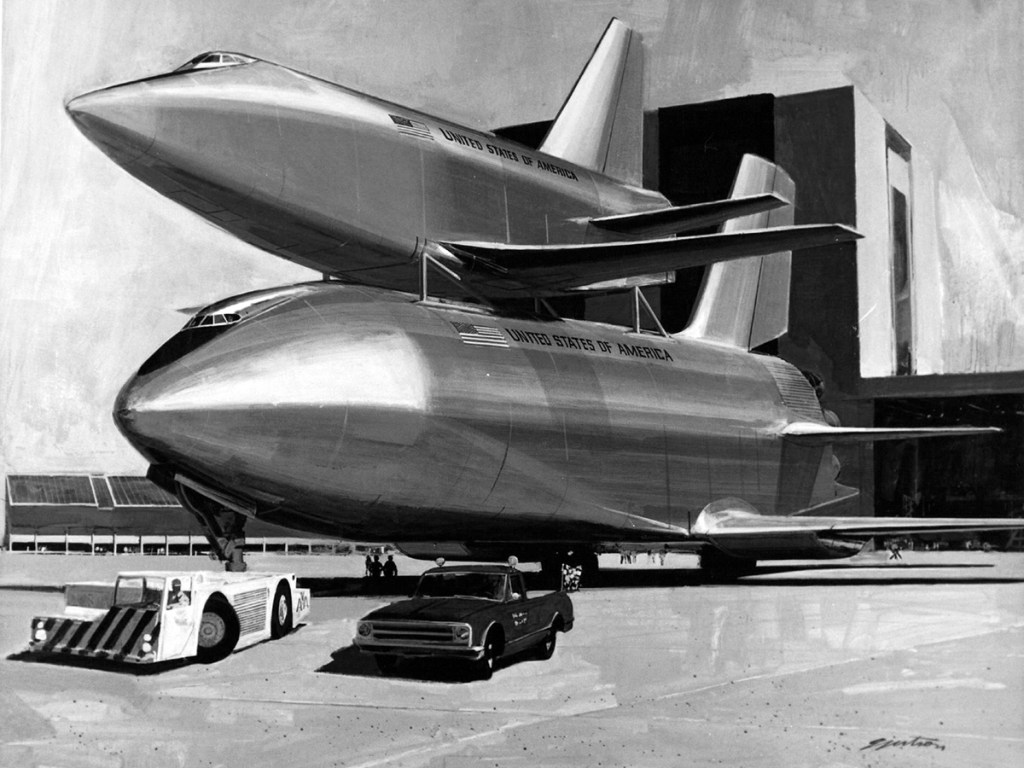

North American’s NAR 161-B orbiter carried a crew of two and up to ten passengers in a forward module. Four deployable jet engines mounted on top of the fuselage gave it a go-around capability. General Dynamic’s B9U booster was a significant evolution of its B8D concept. The straight wing was replaced with a delta wing to improve stability through all phases of the flight. The landing jets were moved from the nose back to the wing to reduce drag.

Alternate Space Shuttle Concepts

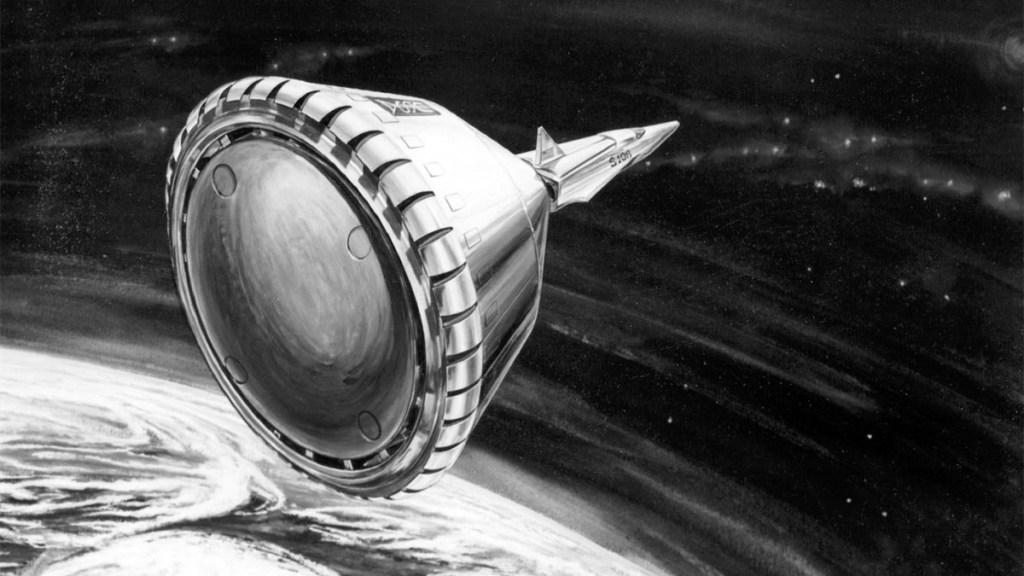

Chrysler

Chrysler’s Single-stage Earth-orbital reusable Vehicle (SERV) was a launch system capable of carrying up to 125,000 lbs of cargo. SERV had a large conical body with a rounded base, covered with ablative screw-on panels. A twelve module LH2/LOX aerospike engine was used during ascent, a ring of jet engines slowed the vehicle’s descent prior to touchdown. The original proposal used a lifting body spaceplane based on the HL-10 called MURP to support manned missions. A later version paired SERV with a personnel module based on the Apollo CSM.

Lockheed

1970 artwork by Boeing artist John J. Olson

After partnering with Boeing for a failed Phase B bid, Lockheed was awarded a contract under the Alternate Space Shuttle Concepts (ASSC) study in July 1970. The study focused on partially expendable designs as a fallback should the TSTO configurations prove too challenging or costly.

Boeing / Grumman

In December 1970 Grumman and Boeing received a contract to study two-stage-to-orbit shuttle configurations using both internal and external liquid hydrogen tanks. In review with NASA, Boeing and Grumman demonstrated that equipping the orbiter with an external drop-tank would lead to a significant reduction in the weight, size, development risk and cost of both vehicles. In April NASA authorized Boeing and Grumman to make a detailed study of the most promising configuration: a three-engine orbiter with an external liquid hydrogen tank and heat-sink booster.

May 1971 – Nixon Ruins Everything

NASA’s budget is capped by the Office of Management of the Budget for the next five years, effectively ending development of a fully reusable shuttle.

September 1971 – Phase B Prime

McDonnell Douglas and North American Rockwell both received contract extensions in March 1971 to study the impact of Grumman’s drop tank concept on their Phase B designs.

While the LS-200 design had been shelved, Lockheed received funds to continue working on drop-tank and solid rocket booster configurations.

Fully-reusable shuttle orbiter with the S-IC used as an interim first stage. Painting by Grumman artist Craig Kavafes.

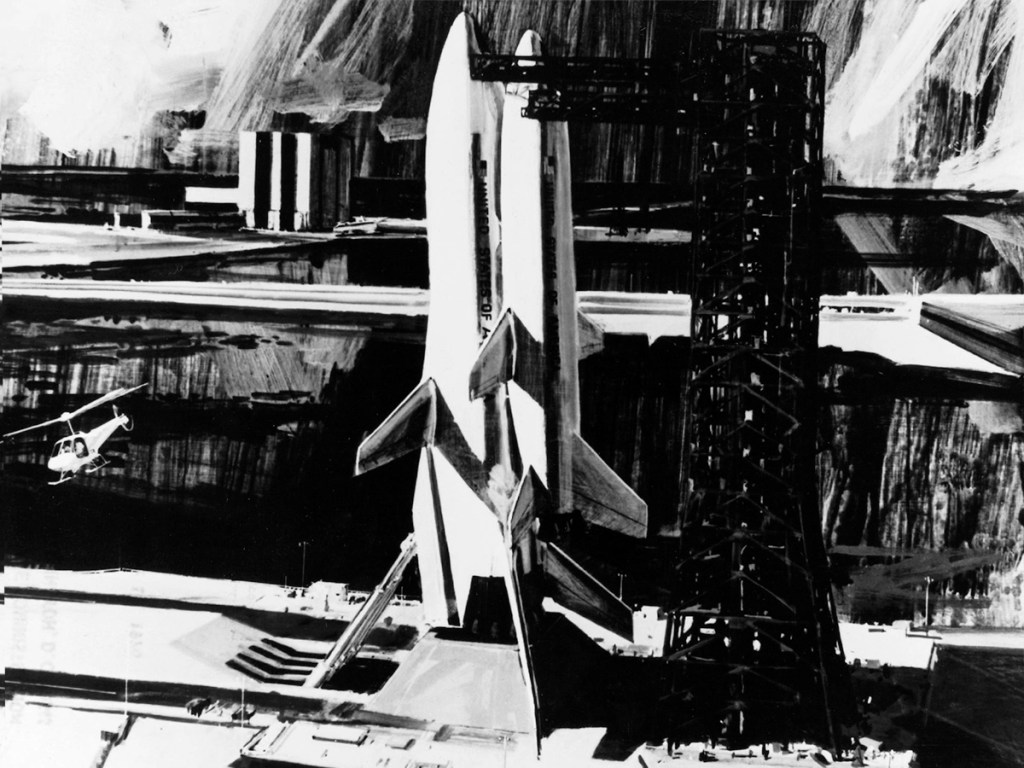

Boeing and Grumman investigated the Saturn S-1C interim booster concept as well as various combinations of drop tanks and boosters. Boeing also unveiled a shuttle booster design in August 1971 dubbed RS-1C, which would have put wings, landing gear and jet engines on the S-1C booster, transforming it into a flyback booster.

Winged S-IC stage. (Boeing)

October 1971 – Phase C/D Request for Proposal

RFPs were sent to Grumman / Boeing, McDonnell Douglas / Martin Marrietta, and North American Rockwell for final proposals for Shuttle full-scale development.

November 1971 – Phase B Double Prime

Grumman / Boeing, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas / Martin Marrietta, and North American Rockwell were issued contracts to study lower cost booster concepts: a fully recoverable booster stage, a modified Saturn V stage to serve as a flyback booster, and solid rocket motors.

March 1972 – Orbiter and Integration Systems

The RFP for development of the orbiters and integration systems was released on March 17, 1972.

“As a design objective,” the RFP stated, “the Space Shuttle System should be capable of use for a minimum of 10 years, and each Orbiter Vehicle shall be capable of low cost refurbishment and maintenance for as many as 500 reuses.”

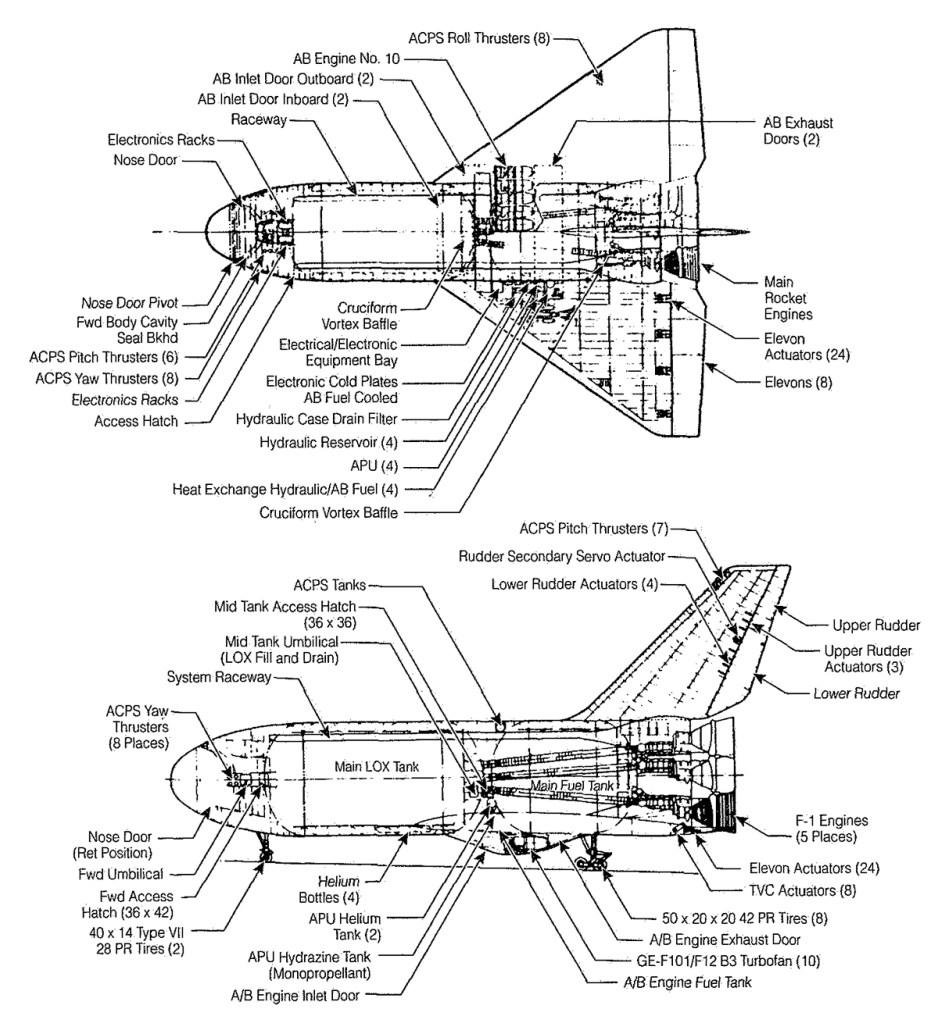

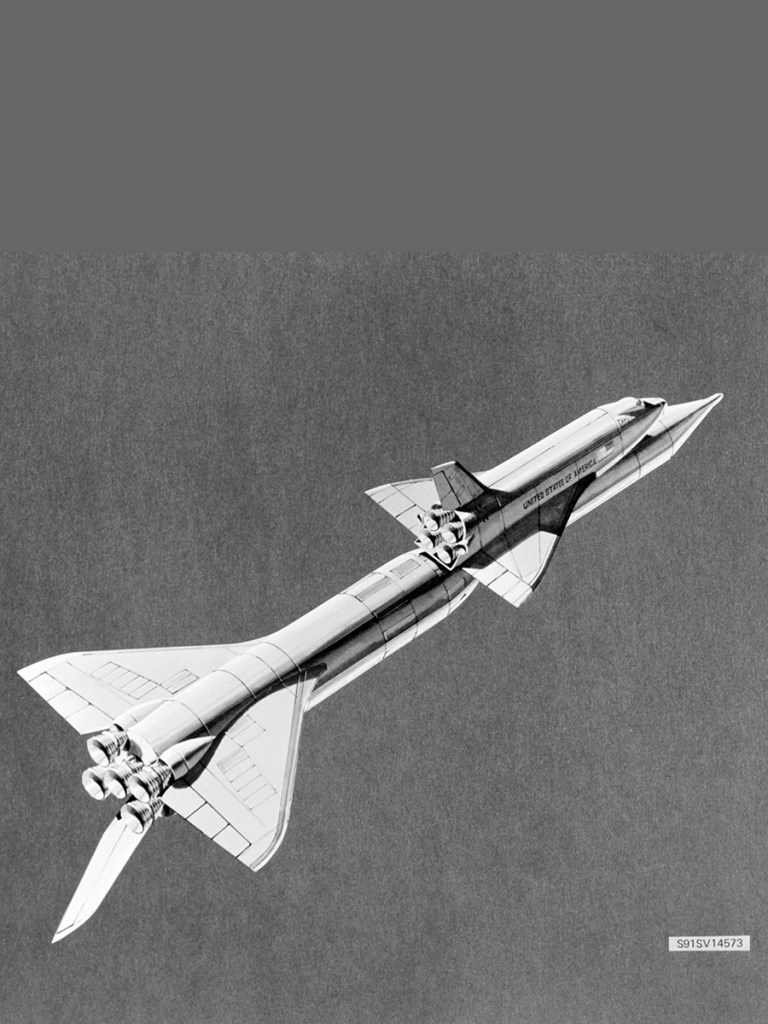

Final proposals by (left) North American Rockwell and (right) McDonnell Douglas.

The responses were due on May 12, and four companies replied: Grumman, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas and North American Rockwell.

Grumman

Grumman gained the highest score in the technical areas. Its structural layouts showed a thorough understanding of potential

problems and positive solutions. Grumman, however, was less outstanding in cost and management, the proposed cost was higher than NASA liked.

Lockheed

Lockheed’s bid ranked fourth in the competition, it was heavy and NASA Administrator James Fletcher considered that

its design had “unnecessary complexity.” Lockheed was also was the only bidder with no experience in building

piloted spacecraft

McDonnell Douglas

The final McDonnell Douglas proposal projected a relatively high cost, and showed technical weaknesses. The provisions in the proposal for maintainability of the Shuttle failed to adequately make use of the expertise Douglas had gained building the DC-10 airliner. McDonnell Douglas came away ranked third in the competition.

North American Rockwell

North American’s concept showed weaknesses, such as a crew cabin that would be difficult to build, but the design provided the lightest dry weight of any of the designs submitted, at the lowest cost of the four.

July 1973 – RFP for SRM

On July 16, 1973, the RFP for design and development of the SRM was issued to Aerojet Solid Propulsion, Lockheed, Thiokol, and United Technologies. NASA selected the Thiokol Chemical

Company.

References

The Space Shuttle Decision T.A. Heppenheimer NASA SP-4221

Shuttle, Encyclopedia Astronautica

Volume IV: Accessing Space Edited by John M. Logsdon, with Ray A. Williamson, Roger D. Launius, Russell J. Acker, Stephen J. Garber, and Jonathan L. Friedman. 1999

One thought on “Space Shuttle: Part 2”