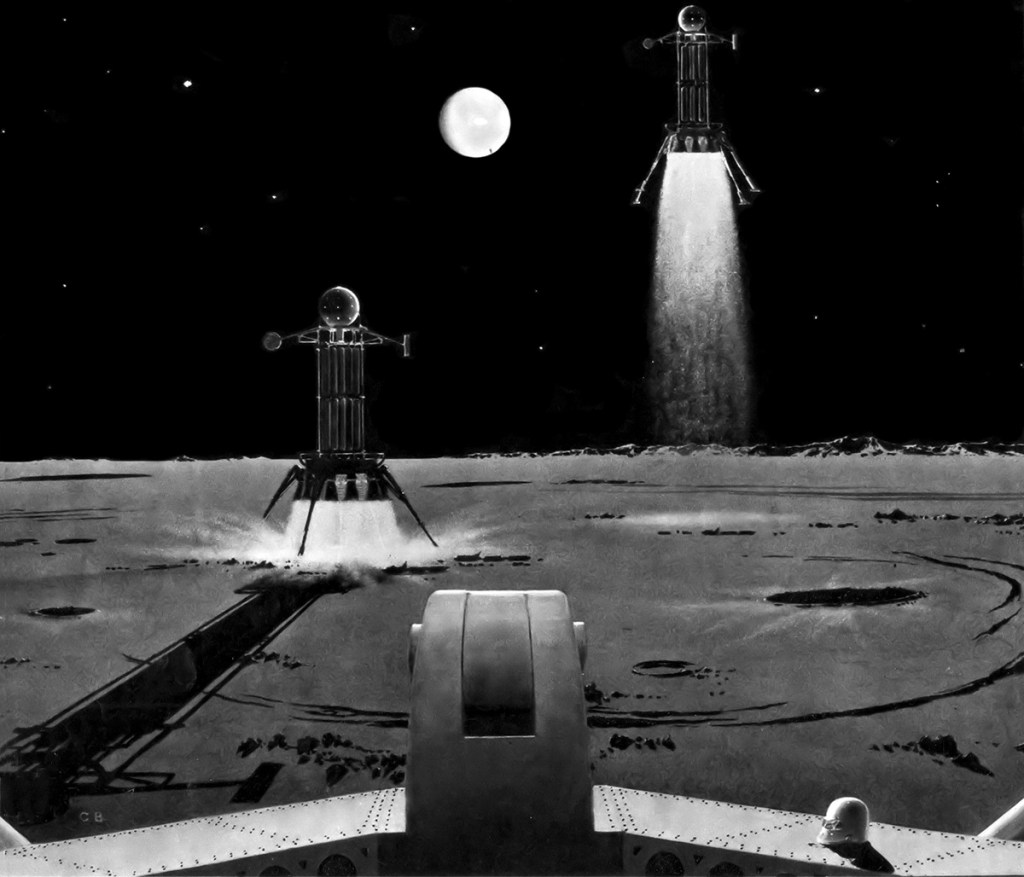

Stunning artwork by Alexander Leydenfrost prepared for a 1946 article in Collier’s Magazine

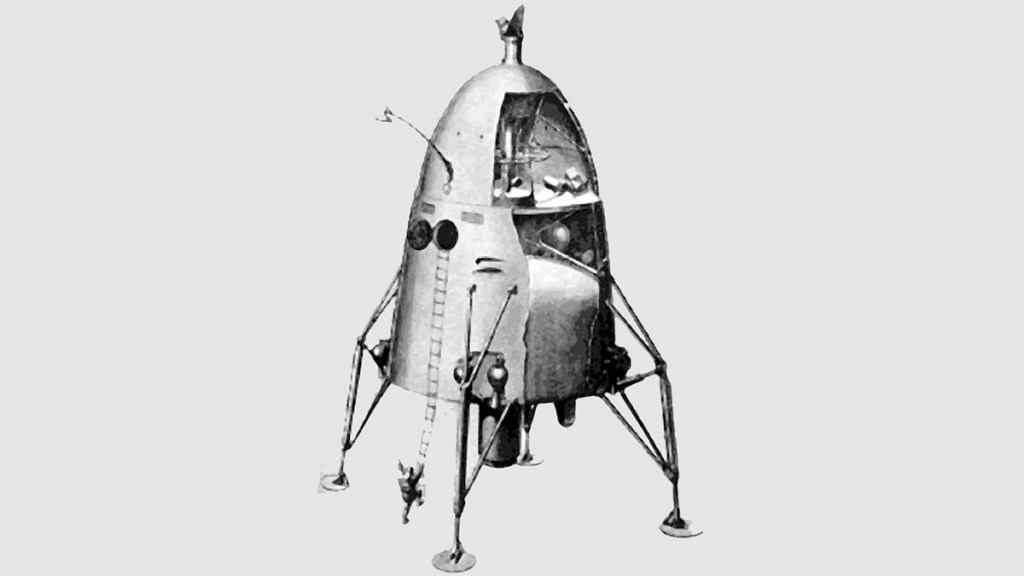

BIS Lunar Spaceship – 1938

In 1938, the British Interplanetary Society Technical Committee began a study that looked at the feasibility of a lunar expedition using existing technology.

The rocket would be launched from a partially submerged caisson, ideally staged on a high-altitude lake close to the equator. High pressure steam would give the vehicle its initial boost, the first step of rockets firing immediately afterwards. Shock-absorbing legs would extend from the base of the crew module for the lunar landing.

The booster consisted of powder rockets, which were shed in steps as they were exhausted, accelerating the vehicle to escape velocity. A sixth step was retained to allow the vehicle to land on the Moon; leave lunar gravity and, and slow velocity prior to re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere. Mounted hydrogen peroxide rockets would fire at stages requiring fine control, with steering provided by steam jet engines. The vehicle would be spun in orbit to create artificial gravity.

The fused aluminum oxide hull of the crew cabin had acrylic windows; the inner hull was lined with layers of resin bonded linen. A ceramic dome protected the cabin during takeoff. Coelostats, developed in part by a young Arthur C. Clarke, provided a steady view of the heavens while the cabin rotated.

The crew were well provisioned for, with food and water for twenty days, although only one plate, cup, knife, and fork were carried to save weight.

Images: British Interplanetary Society

Lunar Lander / Bis Lunar Spaceship

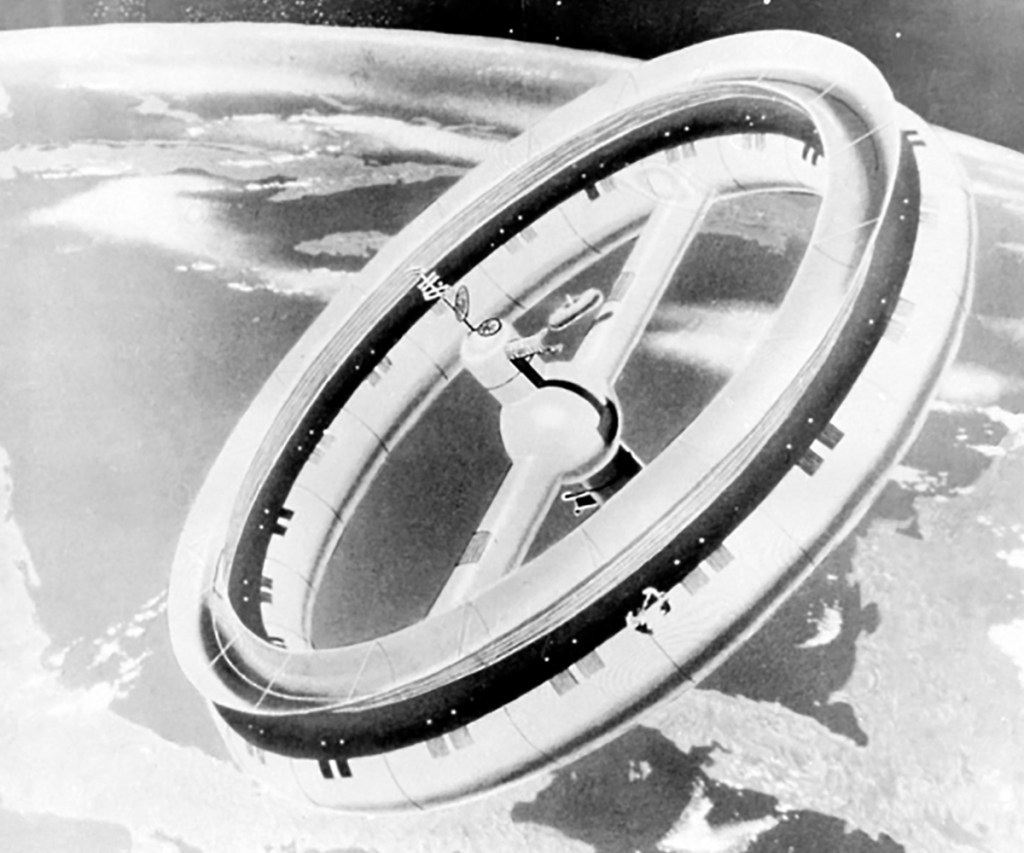

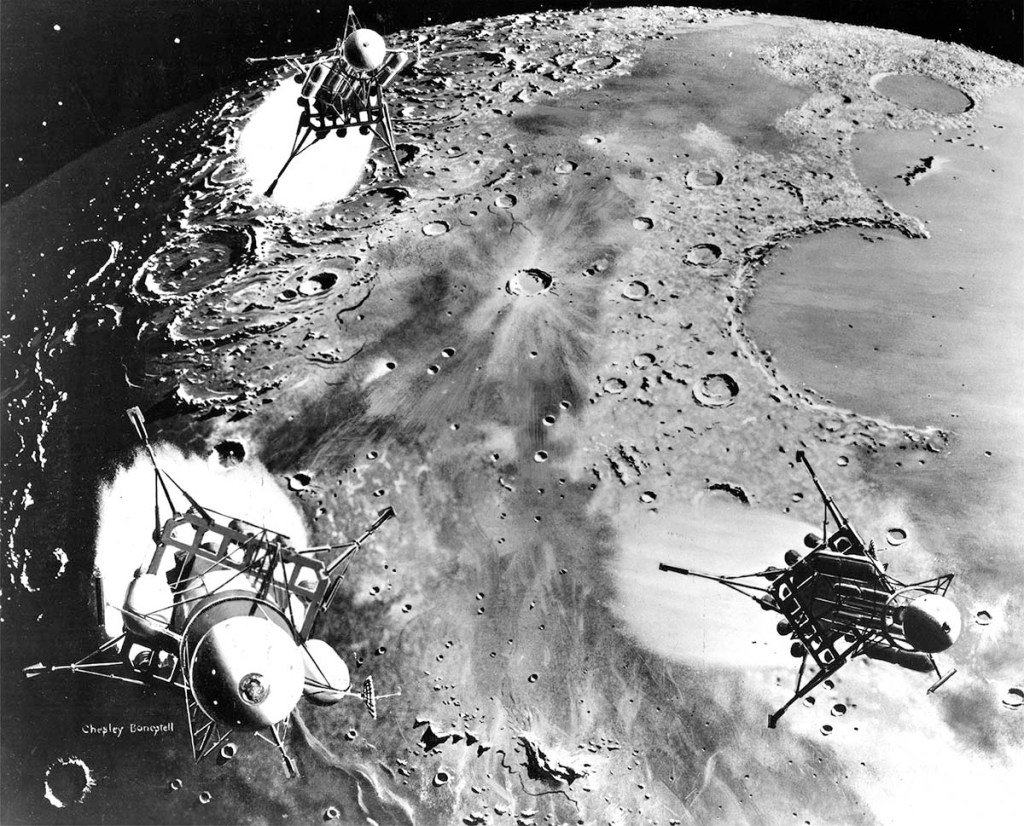

Von Braun Lunar Expedition – 1952

A series of articles published by Collier’s magazine beginning in March 1952 outlined Wernher von Braun’s plans for human spaceflight. The individual articles, edited by Cornelius Ryan, were authored by Willy Ley, Fred Lawrence Whipple, Dr. Joseph Kaplan, Dr. Heinz Haber, and Von Braun. The October issues detailed Von Braun’s plans to explore the Moon.

Werner von Braun’s lunar expedition would be a grand affair, reminiscent of the voyages undertaken during the Age of Discovery.

A 250-foot diameter space station would first be constructed in orbit by a fleet of ferry rockets. Once operational, the station would support the construction of three enormous lunar landers in earth orbit; each lander having the same mass as a Saturn V rocket.

For the voyage, two landers would carry crew and propellant for the return trip; the third is a one-way cargo vessel. Prior to the expedition, a manned orbiter would be sent to lunar orbit to photograph the surface and a suitable landing site would be selected.

Final site selection would depend on the results of the photographic mission, but a site at Sinus Roris was considered the most suitable. Once on the lunar surface, the six-week stay begins with the crew setting up base camp. The cargo vessel is unloaded, and the hold is unbolted and lowered to the ground in sections to be used as underground crew accommodation. Three pressurized rovers provide transport.

With the addition of three trailers of supplies, two of the rovers would take a ten-man team on the trek to the crater Harpalus. Towards the end of the expedition the crew set up automatic telemetering stations, which will continue to radio data back to the earth, before returning to the earth orbiting space station.

Images: Collier’s

Lunar Lander / Von Braun Lunar Lander

Man and the Moon – 1955

Disney employed von Braun as a technical consultant for an episode of Disneyland directed by Ward Kimball, one of Disney’s “Nine Old Men.” The live action portion depicts a reconnaissance mission to photograph the lunar surface. The hero ship, RM-1, would be built in orbit from modular components and discarded parts of the Man in Space vehicle. A dockable bottle-suit was provided for crew EVA.

Images: Dan Beaumont

Lunar Reconnaissance Vehicle / RM-1

Convair Manned Lunar Reconnaissance Vehicle – 1958

Similar in concept to the RM-1, Krafft Ehricke designed the MLRV to chart the lunar surface in preparation for a manned landing.

Images: Fantastic Plastic

Lunar Reconnaissance Vehicle / Convair MLRV

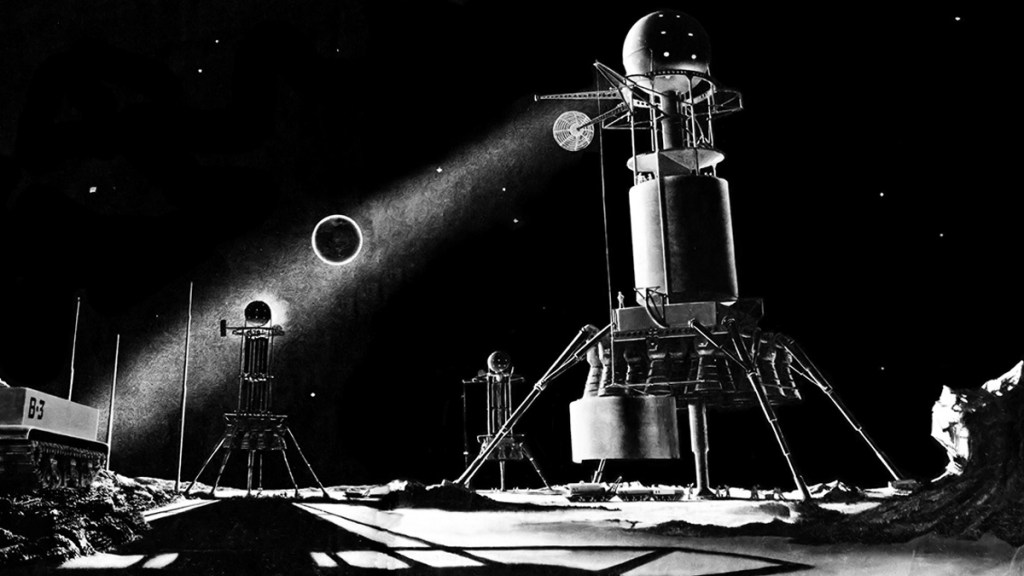

Lunex – 1958-1962

The Lunar Expedition was planned by the US Airforce as a manned mission to establish an underground base on the moon by 1968; essential to demonstrate US technological dominance. The lander – consisting of a manned re-entry vehicle, a lunar landing stage, and a lunar launch stage – would be launched from earth by a three-stage liquid or solid propellant booster to escape velocity on a lunar intercept trajectory. A cargo module without the capability for lunar launch would also be built.

Image: NM Space Museum

Project Horizon – 1959

Not to be outdone by the Airforce, the US Army convened a taskforce in March 1959 with the goal of establishing a lunar outpost by the quickest practical means. Under the direction of Maj. Gen. John B. Medaris of the Army Ordnance Missile Command, and in collaboration of Von Braun’s team, the task force completed a report in June that proposed a manned moon landing in 1965, followed by the construction of an operational lunar outpost in 1966. Construction of the final base would require 61 Saturn I and 88 Saturn II launches, transporting 490,000 pounds of cargo and equipment to the moon.

Images: SOVA

HELIOS – 1959

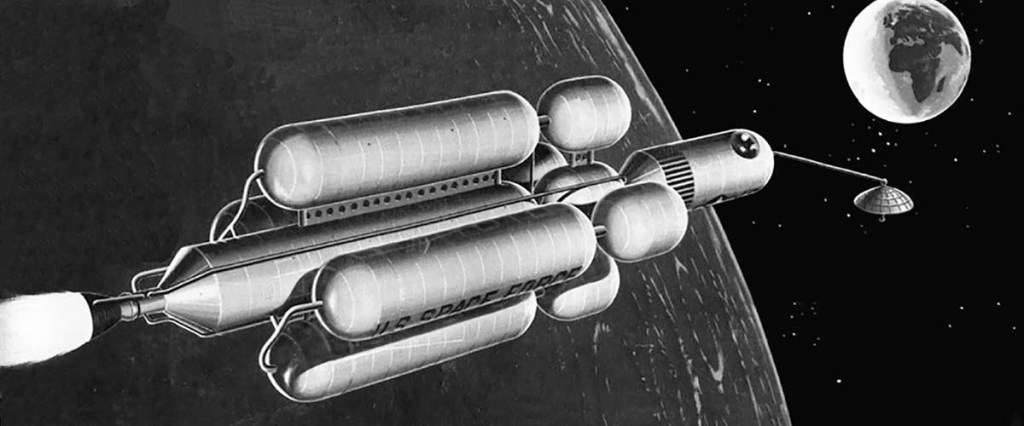

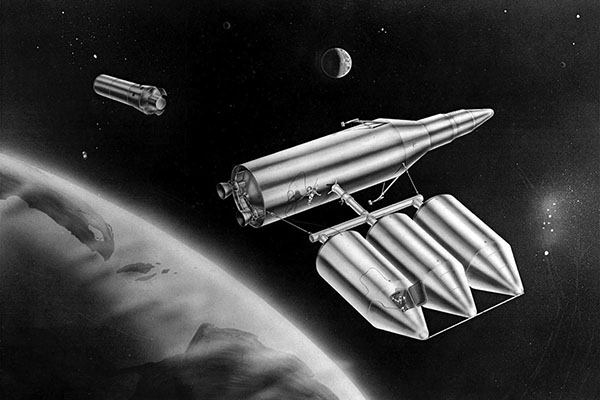

The Heteropowered Earth-Launched Inter-Orbital Spacecraft (HELIOS) was a two-stage interorbital launch vehicle proposed by Krafft Ehricke to deliver crewed modules to the moon. A recoverable booster stage would carry a nuclear second stage to orbit. The second stage would separate from its payload and, relying on distance rather than heavy shielding, tow the crew gondola under nuclear power to a soft landing on the lunar surface.

Image: SDASM Archives

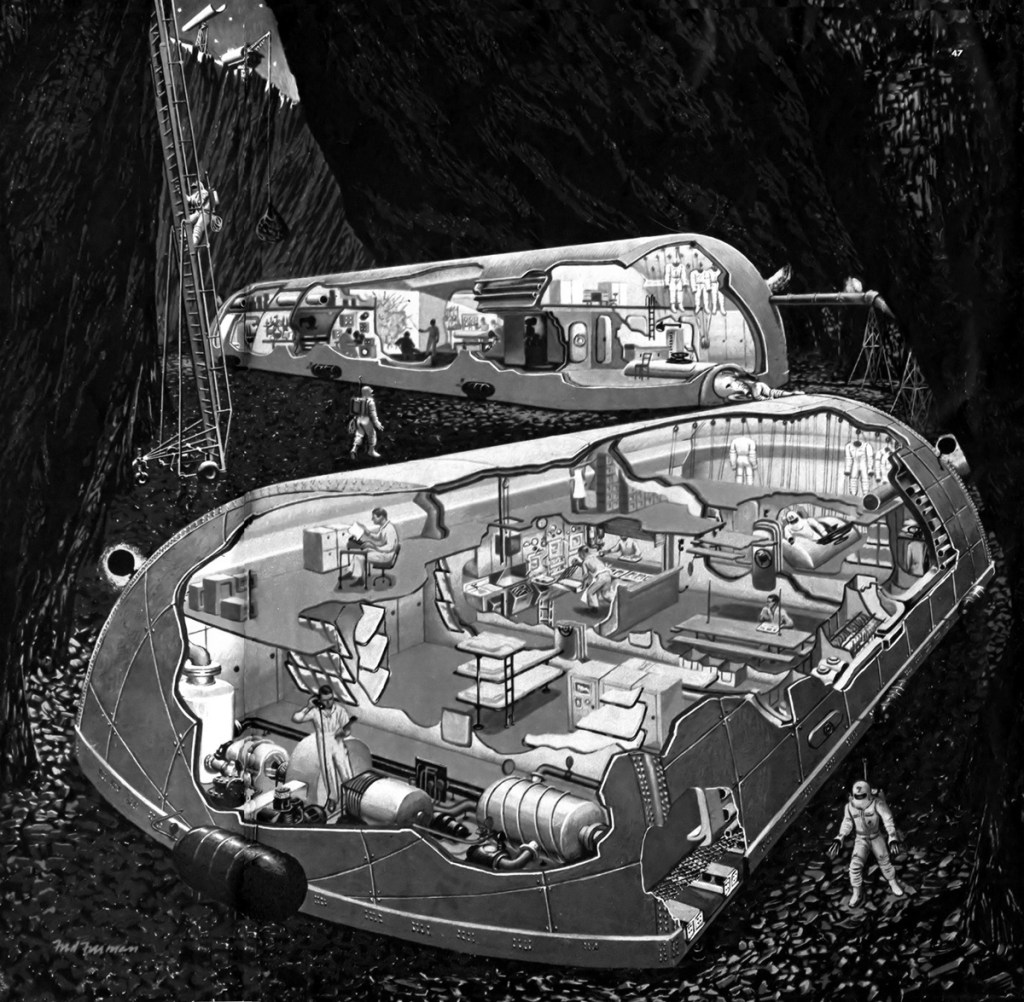

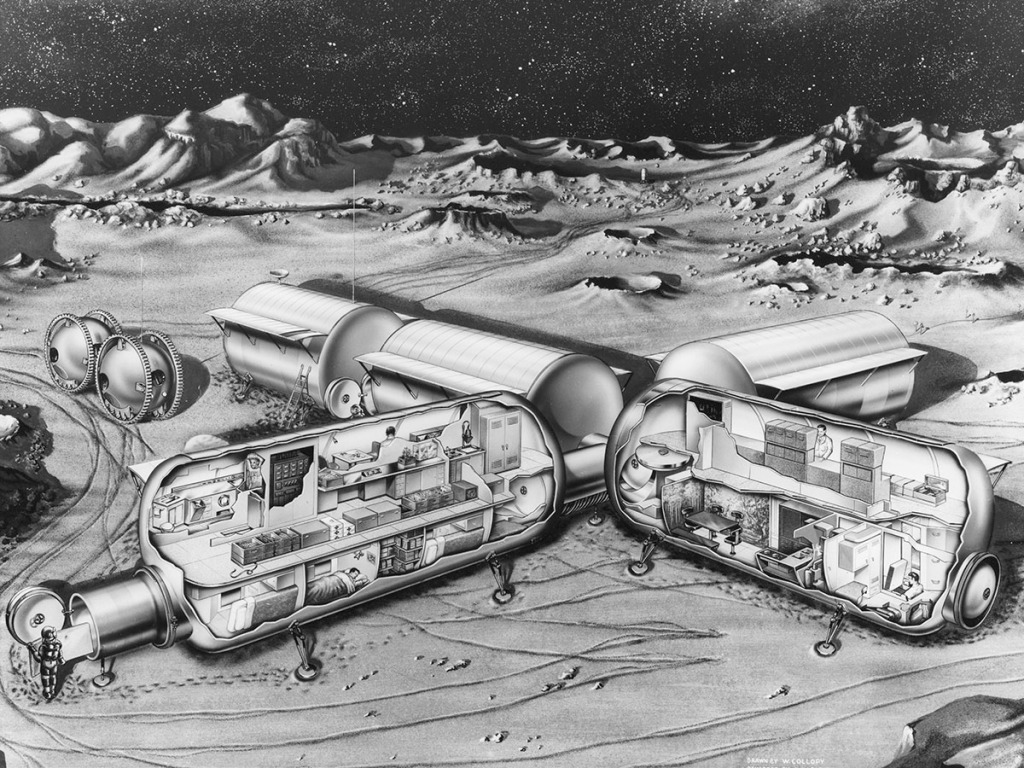

Republic Aviation design for a lunar facility painted in 1961

Lockheed ELO – 1961-1963

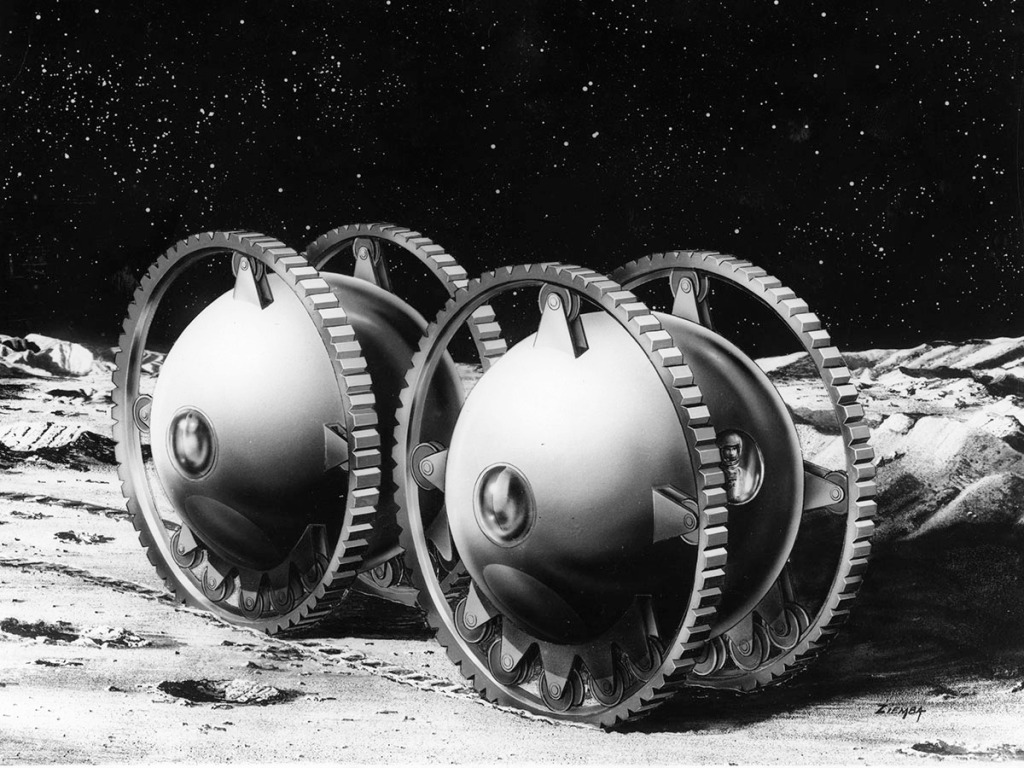

Within a month of John F. Kennedy’s address on May 25, 1961, committing the United States to landing a man on the Moon, Lockheed initiated a series of internally funded feasibility studies to position the company favorably in the expected competition for NASA contracts. The core of these lunar projects was a series of engineering studies that focused on short duration and permanent manned Moon missions. The permanent base was designed to support 100 astronauts in cylindrical modules. The base would be re-supplied by a Saturn C-5 every 30 days.

A spherical, 2-man, lunar tractor would be used for construction and surface transportation. A long-distance flying vehicle would be available for long-distance missions. Power for the base would be provided by a SNAP reactor.

Images: Mike Acs

1964 – Project Selena

In 1964 Philp Bono proposed using the enormous Reusable Orbital Module-Booster & Utility Shuttle (ROMBUS) he was developing at Douglas for a manned lunar mission. The lander ROMBUS would rendezvous in low earth orbit with two tankers and refuel. After a soft landing on the moon, the empty fuel tanks would be used to construct a temporary lunar habitat. The long-term goal of Selena was to establish a 1000-man lunar colony to support the follow-on Deimos Mars expedition.

Images: Numbers Station

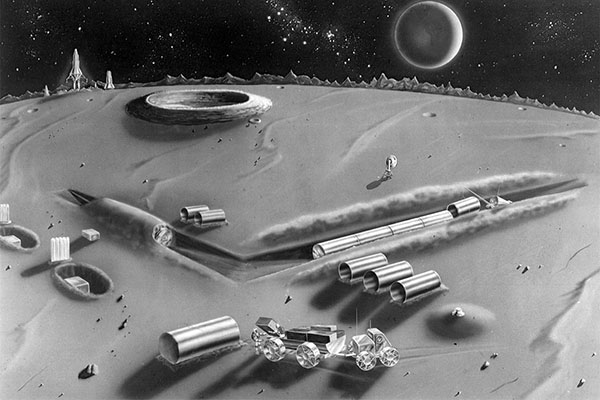

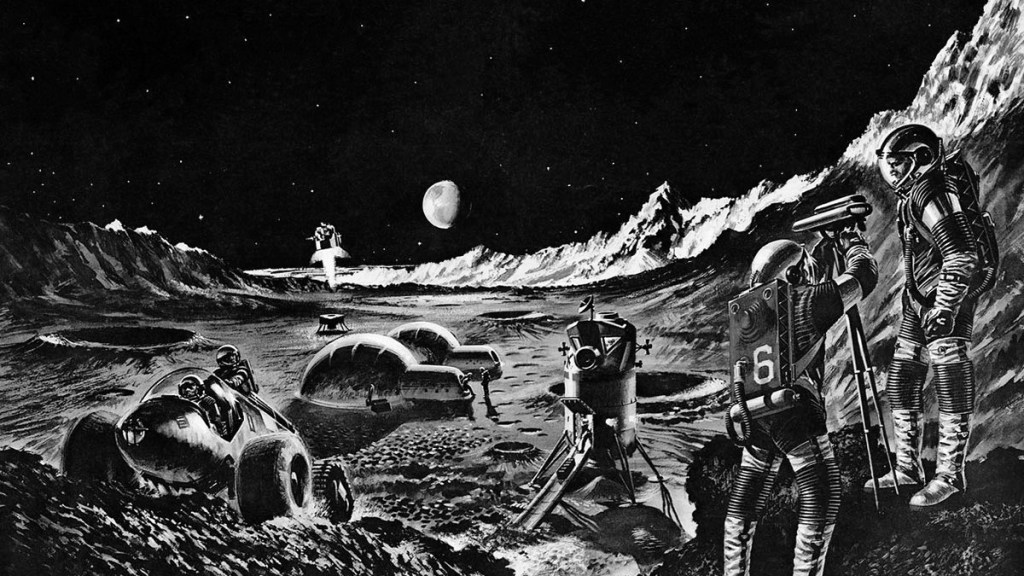

Lunar Base painted in 1965 by Wilf Hardy

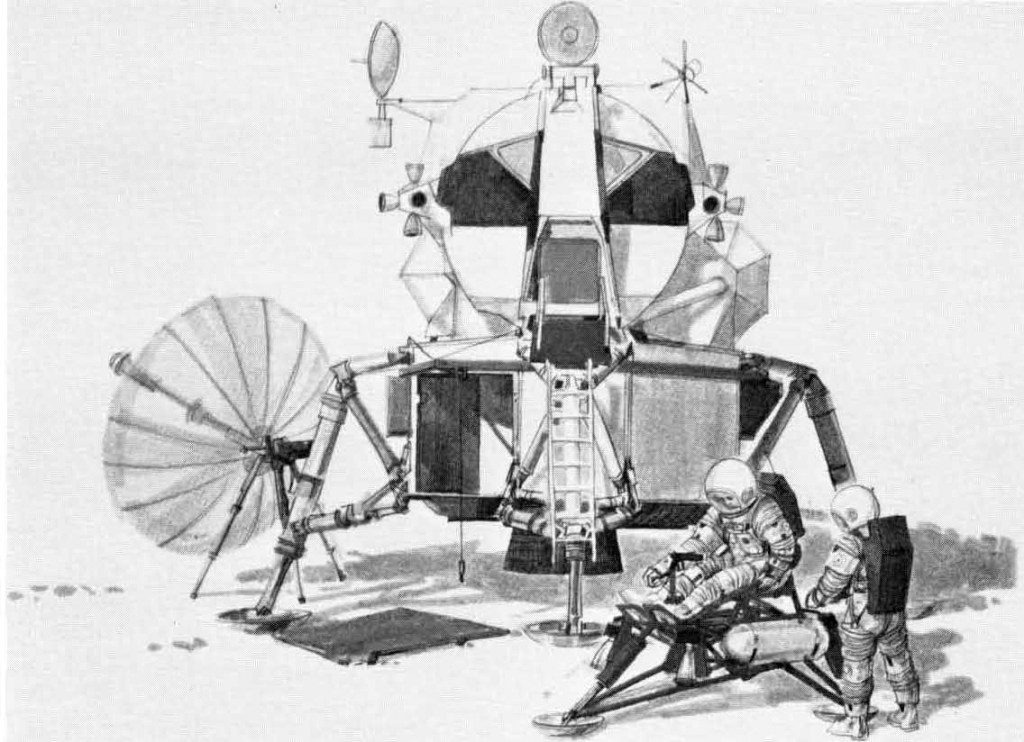

Apollo Applications Program – 1967-1968

The Apollo Applications Program was created by NASA Headquarters to develop science-based human spaceflight missions using Apollo hardware. NASA estimated it would require $450 million in 1967 to fully fund the AAP, with over $1 billion being required in 1968. The Johnson Administration declined to fund it adequately, allocating $80 to the program in Fiscal Year 1967.

AAP Programs

AES (Apollo Extension Series) Lunar Base

Beginning in 1972, NASA would begin a series of lunar exploration missions using a version of the Apollo LM modified for extended stays of 3 to 4 days. A 28-day lunar survey mission would be flown in 1974. Beginning in 1975, dual-launch crewed missions would begin: A Saturn V launch would deliver a manned Apollo CSM and LM Shelter to lunar orbit. The CSM would transpose and dock with the LM Shelter. Once braked in lunar orbit, the un-crewed LM Shelter would separate and land autonomously. A second Saturn V launch three months later, using an Extended CSM and a LM Taxi, would transport a crew to the LM Shelter for surface visits of up to a fortnight.

Vehicle Development

Extended CSM. A CSM would be refitted to provide enough consumables to operate with one astronaut for up to 30 days in lunar orbit.

LM Shelter, an Apollo LM with three-month quiescent (inactive) capability. The ascent stage engines and associated tankage would be removed and replaced by consumables and equipment to accommodate two astronauts for up to 14 days.

Apollo LM Taxi, an Apollo LM would be modified to give it a 14-day quiescent lunar stay time, with 3 days of operational use. The Taxi would be shut down after landing, and reactivated two weeks later when the crew would return to the CSM.

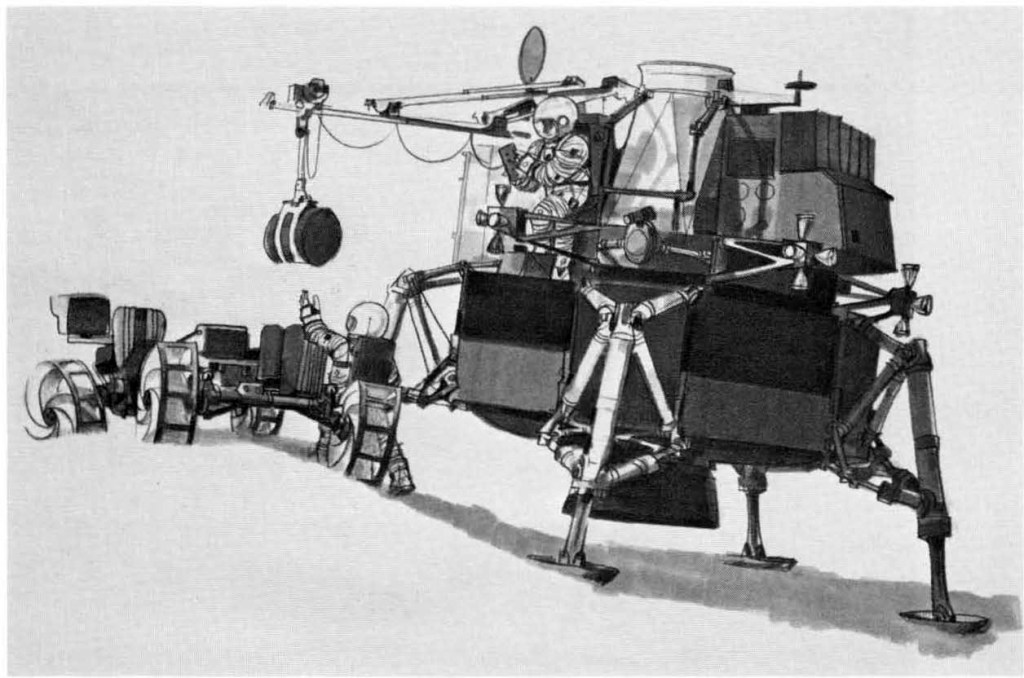

Lunar mobility vehicles that could be accommodated in the payload bay of the LM Shelter would be developed.

ALSS (Apollo Logistics Support System)

Developing the LM into a dedicated cargo truck would allow delivery of loads up to 11,000 lbs to the lunar surface, this would mean larger surface shelters and pressurized vehicles could be landed enabling stays of up to 30 days.

Vehicle Development

LM Truck, a Lunar Module descent stage adapted for unmanned delivery of payloads to the lunar surface.

MOLAB, a pressurized rover, would provide the crew with mobility and shelter during long-range lunar traverses.

A Lunar Flying Vehicle (LFV) would give the crew the means of returning to the LM Taxi should the MOLAB vehicle became disabled.

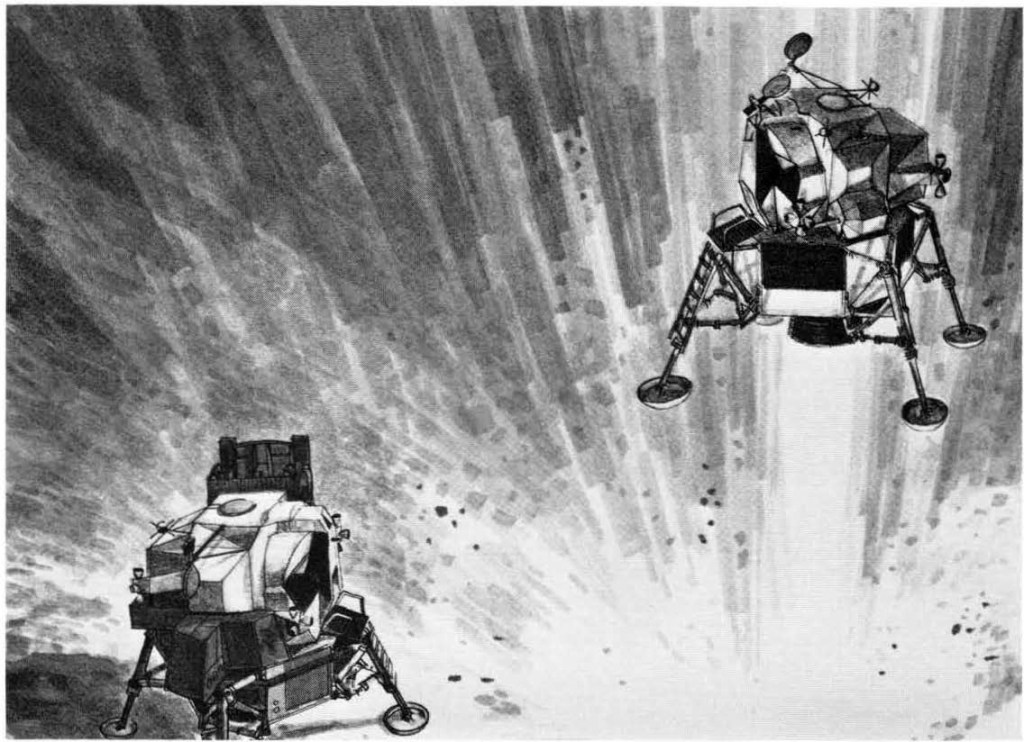

LESA (Lunar Exploration System for Apollo)

In the final evolution of the AAP, a new lunar lander would be developed taking full advantage of Saturn V’s trans-lunar payload capability. With a payload capacity of nearly 28,000 lbs., the new LLV would be capable of carrying life support systems, consumables, shelter, and a Lunar Roving Vehicle to the moon on a single launch. The new vehicle would give astronauts a 90-day exploration window. Once the LESA landed, a crew of three astronauts would arrive to make it operational and deploy the LRV. Traverses as far 400 km could be undertaken from the base. Later models would allow for an 18-man installation to be built, manned over 24 months by a revolving crew.

Images: NASA Images, Mike Acs, Numbers Station